By Xavier Richet, University Sorbonne Nouvelle, BRIC Seminar, MSH-EHESS, Jean Monnet Chair

Sintesi

Il seguente contributo presenta l’iniziativa One Belt One Road mettendo in evidenza la sua genesi, le motivazioni di fondo analizzate attraverso diverse chiavi di lettura, i metodi di finanziamento e i processi di implementazione. In seguito l’autore discute le ragioni e gli impatti della presenza cinese a livello economico e progettuale nello spazio post-sovietico. La Cina opera in tale spazio orientandosi da un lato verso i mercati maturi dell’Europa e dall’altro verso l’accesso alle materie prime dei paesi dell’Asia Centrale. Nella sua complessità il progetto OBOR presenta diversi aspetti di criticità che sarà necessario affrontare. Innanzitutto i canali commerciali coinvolti nel progetto attraversano uno spazio immenso che rientra principalmente nell’area post-Sovietica, la quale è attualmente frammentata in zone dalle caratteristiche istituzionali ed economiche radicalmente diverse fra loro. Inoltre, il progetto è costretto a confrontarsi con i piani di integrazione regionale della Russia. Infine il progetto mantiene dei tratti di indefinitezza per quanto riguarda il suo assetto istituzionale.

Introduction

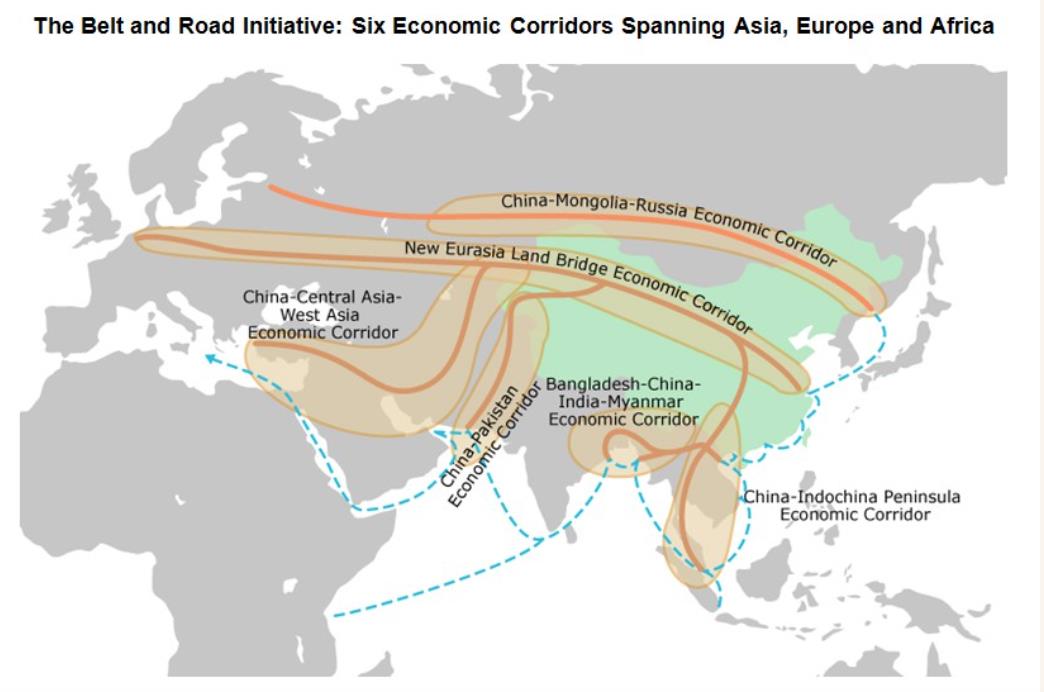

This contribution presents the general objectives of the ambitious project carried out by the current Chinese government, the One Belt, One Road Initiative (OBOR), its design, the motivations behind it, the financing methods and its implementation (first section). The project envisages two roads, one terrestrial and the other maritime. The land route, itself divided into several roads (“All roads lead to Rome” ...) crosses Central and Western Asia. It crosses into Asia large areas, economies rich in raw materials but sparsely populated and less developed, some of which were republics of the former Soviet Union. In Europe, it also crosses or runs along former Soviet republics and countries formerly under the control of the USSR (the “Eastern Countries”), now members of the European Union. In a second section, we discuss the motivations and impact of this Chinese presence in terms of exchanges, projects and industrial spin-offs in the post-Soviet space of Central Asia. In conclusion, we will highlight the variety of modes of entry, the differentiated impacts of the Chinese presence in the regions crossed by the New Silk Road which still remains a project whose realization raises many questions.

An ambitious and global project with variable geometry

In 2013 the Chinese leaders announced the launch of the OBOR Initiative or New Silk Road (NSR). It is an ambitious project with regard to its objectives, the scope covered, the resources mobilized, the associated partners, the conditions for its implementation, the necessary investments and the level of risks incurred. This project is part of the rise of the Chinese economy today which is one of the main engines of growth in Asia and the world. The level of development achieved over the past three decades and the level of accumulated financial reserves now makes China an indispensable actor in shaping trade and capital movements at the regional and global levels, and especially in the post-Soviet economic space.

This project would also be a response to recently signed trade agreements (TPPs) or negotiating agreements (TTIPs) developed under the initiative of the United States, which implicitly seeks to marginalize China. The future US administration intends to withdraw from the TPP agreement.

Figure 1 : The New Silk Roads

Source : Simola Heli (2016)

Who grasps at too much loses everything ? OBOR initiative encompasses, in a broad sense, 65 countries and concerns 4.4 billion people. Some commentators have drawn a parallel between the Marshall Plan implemented by the United States after the Second World War to rebuild the European economies. For others, the OBOR initiative would illustrate China's hegemonic ambitions.

Other explanations, of a Leninist type, point to the need for China to find outlets for industrial overcapacities in several sectors and provinces, in industries in which China has created certain competitive advantages (railway industry, steel, cement, aluminium) and whose profitability domestically is today is declining. It is estimated that an additional 60 billion dollars would be required to utilize surplus capacities in the steel sector alone.

The OBOR project is also the mean to perpetuate the export-led growth model by relocating intensive labor productions to nearby countries (Vietnam, Cambodia), as labor costs are rising in China. The project also has a regional dimension in seeking to involve the less developed provinces of western China and making them regional hubs from where the new rail routes will start to conquer markets through rail transport in Central Asia right to Western Europe.

The project has a strong regional dimension: for many years, China has secured raw material supplies by signing trade agreements with neighbouring countries (Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Laos, Burma and others). The implementation of this project allows it to intensify exchanges and integrate with its Central Asia partners by creating a gravity effect. This raises the question of how to articulate development and regional integration and optimize the use of new railway lines with distant European markets.

Various types of financing are mobilized to support this , most of which are provided by Chinese institutions: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which has a capital of 100 billion dollars, The Silk Road Fund with an the amount of 40 billion dollars, financed by three Chinese banks: China Investment Corporation, Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank. The New Development Bank, founded by the BRICS with a 100 billions dollars, can also contribute to the financing.

Western institutions participate in the financing: the Asian Development Bank, the EBRD, the World Bank. Financial institutions from Central Asia countries are also contributing. Currently, China has invested more than 890 billion dollars in 900 projects involving 60 countries.

This project raises many questions concerning the time horizon, the modalities of its implementation, the types of cooperation to be developed, the level of resources to be mobilized, their financing and their profitability, the level of sunk costs induced by risky investments in some coutries like Pakistan. Optimal infrastructure management is another technical and economic problem, in particular the creation of intermediate relays between several destinations, the full use of rail transport, and the control of their costs. If it is shorter to transport a container by rail than by boat (15-18 days against two months), the cost is twice as high. The trains currently traveling do not use their full load capacities. Finally, with what to fill Chinese trains back from Moscow? What can be loaded in Kazakhstan to supply the markets further west?

Lastly, we should mention the governance of this project. How associate partner countries which have different aims are involved in the project? Among the countries concerned, there are risky and economically weak countries (Pakistan), strong and suspicious countries (Vietnam, India, Iran), countries with unstable alliances (Turkey), countries under the umbrella of other great such as the countries within the Eurasian Economic Union recently created at the initiative of Russia.

The post-Soviet space and the New Silk Road

Among the 65 countries targeted (The Economist, 2016) by this ambitious project, the countries that make up the post-Soviet space are all present (may be with the exception of Ukraine). They are or will be, to varying degrees, concerned with its realization. These countries come today under different institutional configurations. Russia, along with Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, founded the Eurasian Economic Union. The other former Central Asian Republics, like Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, are not members, neither Georgia nor Azerbaijan, while, in Europe, Ukraine and Moldova are not associated. The former Baltic republics (Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia) joined the European Union with the former « Eastern countries », which were formerly under Soviet trusteeship (the CEECs). With these countries and those of the former Yugoslavia, China founded, at the end of the road, an association called Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries (16 + 1).

Finally, in 2001 China initiated the establishment of an Asian regional intergovernmental organization, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization comprising Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, and, since 2016, also India and Pakistan.

OBOR and the Central Asian Stans

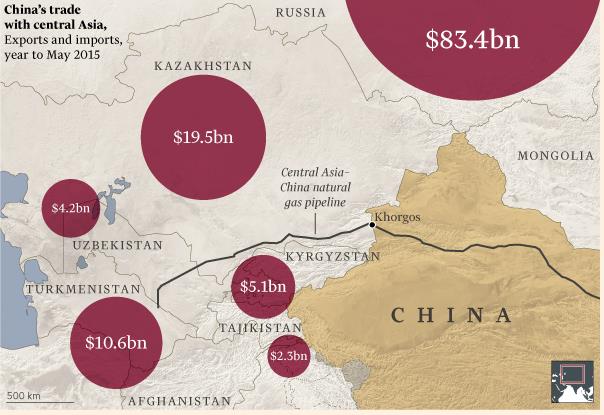

Endowments of natural resources (gas, uranium, petroleum, etc.) attracted the Chinese presence in Central Asia well before the launch of the OBOR initiative. China has secured its supplies to fuel the strong growth of its economy. China's participation in the development of the energy sectors contributed to the strong growth of trade (Figure 2). Over the past decade, trade between China and Kazakhstan has increased from $ 5 billion to $ 20 billion, from $ 0 to $ 10 billion with Turkmenistan, from a few hundred million to nearly $ 5 billion with Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan's $ 2 billion. Over the same period, Russia's trade with Kazakhstan grew from $ 8 billion to $ 20 billion; They have made very little progress, or even stagnated, with the other Stans (Financial Times 2015).

For these countries, cooperation with China is also a means of relaxing the dependence on Russia which was at the initiative of the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). The countries of the region, notably Kazakhstan, are hard pressed to cope with this dual dependency: devaluation of the currency, the impact of the Russian economic crisis, and Chinese pressure to obtain benefits (leasing of lands). Today, in hydrocarbons, China represents more than 30% of investments in the country. For other countries such as Kyrgyzstan, cooperation with China allows for infrastructure development (Box 2), reducing dependency with Russia. The Kyrgyz economy is also strongly affected by the Russian crisis, especially with the drastic decline in transfers of remittances from Russia.

Figure 2 : Commercial exchanges between China and Central Asia.

Source : Financial Times (2015)

The relationship with Russia is certainly the most problematic because of the competition / cooperation relations that stem from the strong economic presence of China in this Union, and in the strong asymmetries that follow. China imports raw materials, it brings capital, infrastructure and actually integrates these economies, reducing the scope of the economic choices of each country, and their specializations. To the contrasting economic dynamics are added the level of resources available, the geopolitical stakes, the desired coherence between the construction of a new economic space (Eurasian Economic Union) and the linkage to the OBOR project. Recent negotiations between China and the Economic Commission of the new Union have addressed a number of issues related to trade and investment, leaving aside the issue of a free trade agreement, which is still a very sensitive issue for Russia and the countries of Central Asia because of the high level of protectionism. For Russia the benefits of EEU cooperation with the OBOR project are greater than the risks involved even though it is inevitable that China will become the main investor in Central Asia and the main market for the region's vast natural resources .

In addition, Chinese objectives, including the construction of fast rail lines to reach Europe, compete with the existing lines (Trans-Siberian). Russia intends to integrate in this project the development of the eastern regions of Siberia, as far as Vladivostok. The construction of a high-speed Moscow-Kazan train by China (originally to be financed by Russia and built by Germany) is the cornerstone of this cooperation between the UEE and the OBOR project. This high-speed train should link, in the future, Moscow to Beijing.

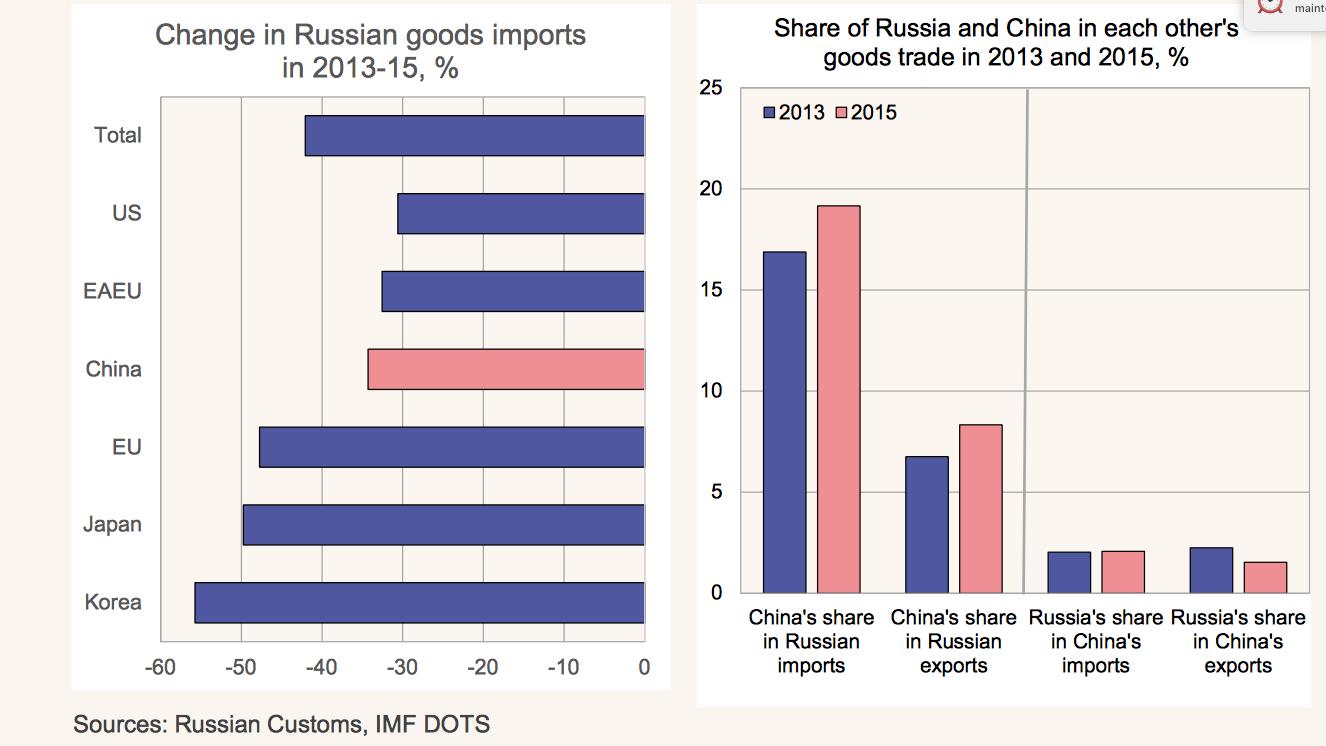

Table 1: Trade between China and Russia: moderate and unbalanced

Source : Simola Heli (2016)

At the moment, the Asian pivot envisaged by Russia does not yet translate into an increase in trade flows. Trade remains at a relatively low level, unbalanced in favor of China (Table 1). Foreign direct investment also shows a strong imbalance, with the Chinese investing in more diversified sectors, reflecting the practice in other parts of the world, notably in Europe (Richet 2016). Agreements for the conveyance of Russian gas to China involve large investments, notably the construction of a gas pipeline (Power of Siberia 2), but there are still differences of view on the roads to be borrowed. Ultimately, Russia should become China's gas supplier up to 30% of its needs. Strictly speaking, these agreements relate to bilateral relations between the two countries and not necessarily within the framework of the OBOR project.

Finally, further west, but still in the EEU, Belarus intends to benefit from the customs union established by the EEU, since trains from China and heading to Europe will only have to cross two customs posts (China-Kazakhstan, Belarus-Poland).

Again, account must be taken of the fact that bilateral investments or exchanges carried out in the countries crossed are not necessarily directly involved in the OBOR project. For example, the private Chinese automotive company Geely builds cars in Belarus. This investment is not included in the OBOR project but it is part of the outsourcing strategy of Chinese firms.

Box 1: Some projects in the field of infrastructure built with Chinese capital and Central Asian countries.

-High-speed train Moscow-Kazan. Construction of a 770 km high-speed railway line. US $ 375m contract won by a Chinese consortium to build the first tranche. Total cost of investment: $ 16.7 billion. The total cost of construction of the Moscow-Beijing line is estimated at $ 100 billion. |

Conclusion

From this brief description of China's presence in the post-Soviet Central Asian region, we highlight the following issues. The new silk roads cross an immense space which, for the most part, composes the post-Soviet space, now fragmented with several institutional contours, very strong asymmetries and differentiated economic dynamics. China operates in this space in two ways: a route to mature markets (Europe), and access to the needed raw materials (Central Asia). The economic repercussions for the countries they pass through are still difficult to assess, however it is clear that they will not fill the imbalances between these countries and China. However, the structuring and specialization effect they entail undermines the regional integration projects borne by Russia. The project, although ambitious and endowed with important resources, remains vague as to its choices, its duration, its institutional anchorage. It is largely dependent on factors internal to China (declining economic growth, new model of intraverted growth), and on uncertainties of the global economy.

References

Duchâtel Mathieu et alii (2016) : Eurasian integration : Caught between Russia and China, www.ecfr.eu/article/essay_eurasian.

Ernst & Young (2015) : Riding the Silk road : China sees outbound investment boom. Outlook for China’s outward foreign direct investment, Global Markets – EY Knowledge, Beijing.

Financial Times (2015) : « China's Great Game: Road to a new empire », 12 oct. 2015.

Johnson Christopher (2016): President Xi Jinging’s « Belt and Road » Initiative. A Practical Assessment of the Chinese communist Party’s Roadmap for China’s Global Resurgence, CSIS, Washington DC.

Questions internationale n° 82 (2016) : L’Asie centrale. Grand jeu ou périphérie, Paris, La Documentation française.

Richet Xavier (2016): « The Belt and Road Initiative and EU-China Economic Relations : Trade, Finance, FDI », International Symposium on Economic Developement of BRICS, Fudan University, Shanghai 20-21 April.

Richet Xavier (2016): “Geographical and Strategic Factors in Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in Europe“ in Richet Xavier, Mustafa Özer, Zoran Grubišić, Ivana Domazet (sous la direction de) (2016):Europe and Asia : Economic integration prospects, Nice, CEMAFI International.

Simola Heli (2016): Economic Relations Between Russia and China – Increasing Interdendancy?, Bruegel, Brussels.

The Economist (2016) : « One Belt, One Road : An Economic Roadmap », Economic Intelligence Unit.