By Xieshu Wang[1]

Introduction

China is the only country that has so far developed a full value chain of electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing, from raw material production, battery making, EV assembly to end-of-life recycling. It’s largely the merit of strong and comprehensive industrial policies, covering multiple aspects from raw material management, general emission standards, EV technical requirements, taxation exemptions, practical advantages to charging infrastructure, public fleet, demonstration zones, etc. These policies have evolved with the market status, following the Chinese way of ‘learning from experimentation’ (Roland, 2000; Qian, 2002; Wang and Yang, 2023), constantly adapting to changing situations. Industrial data about the Chinese EV market’s different dimensions illustrate how effective the EV industry policy has been. To better understand the indispensable role of the industrial policy, we need to trace the origin of China’s EV industry policy and analyse the different types of measures adopted at different government levels. We see that the industrial policies have gone through several phases, showing important changes and evolutions, with the goal to not only reinforce China’s leadership in the emerging global EV industry but also accelerate the decarbonisation of its economy.

Impressive growth of EV production and consumption in China

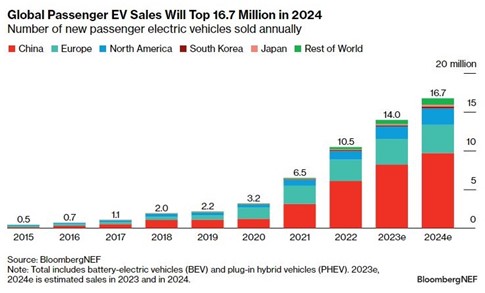

China has become the world’s leading EV production and consumption country in 2015 and has continued to be so since then (see Figure 1). For the year 2023, about 9.5 million units of EVs were sold in China, representing about 32% of total new car sales and showing a growth rate of 38% on a year-to-year basis; among them 7.7 million units were passenger EVs, indicating the dynamic market demand from private sectors (CAAM). In comparison, the estimations for passenger EV sales in Europe and in the North America in 2023 were respectively 3.3 million and 1.6 million units (O’Donovan, 2023).

Figure 1: Annual global passenger EV sales

In fact, the take-off of the Chinese EV industry hasn’t been an easy endeavour. Although China has already identified the EV industry as a future strategic sector back in the 1990s (Gong et al., 2013), the lack of key technologies and key components production capacity has delayed the real progress. Yet, under strong policy orientation, both public and private sectors have continued to invest massively in the industry, and a series of R&D programmes and collaborations dedicated to EV were funded, gradually building manufacturing capacity and purchasing necessary technologies and savoir-faire to make the wheel run. As a decisive move, in 2009, the Chinese central government has announced the first explicit industry policy in support of the local deployment of EV in selected pilot cities. In parallel, regulations regarding EV production’s efficiency and technology standards were released regularly to provide guidance to industrial actors and investors.

Since 2015, China has seen an impressive fast growth in the domestic EV production and sales and has become the largest EV producer and consumer market in the world (see Table 1). In recent years, the EV sector has made significant contributions to the growing auto exports of China. In 2023, China has taken over Japan, becoming the world’s largest auto exporter.

Table 1: Chinese auto/EV production and export

|

Unit: million |

Total Production |

Total export |

EV production |

EV Export |

|

2023H1 |

13.25 |

2.34 |

3.79 |

0.8 |

|

2022 |

27.02 |

3.11 |

7.06 |

1.12 |

|

2021 |

26.08 |

2.01 |

3.54 |

0.59 |

|

2020 |

25.22 |

0.99 |

1.36 |

0.22 |

|

2019 |

25.72 |

1.02 |

1.24 |

0.25 |

|

2018 |

27.82 |

1.04 |

1.27 |

0.15 |

Source: CAAM

A comprehensive package of EV industrial policies

China’s industrial policy aimed at building the technology supremacy in the EV manufacturing and nurturing a completely self-controlled EV supply chain has started to brew in the 1990’ and finally took form in the late 2000’. Its objectives also include mitigating environmental problems mainly in big cities and reducing oil import dependency. During the ‘Tenth Five-Year Plan’ period (2001-2005), China implemented the ‘Major Science and Technology Project for Electric Vehicles’ (863 Plan), forming an overall new energy vehicle technology roadmap. Since 2009, a series of monetary and non-monetary measures have been taken by the central and local governments to incentivise the take-off of local EV markets, expanding very soon from pilot cities to the whole nation and from public sectors (buses, taxis, city sanitation, postal trucks and government officials’ vehicles) to various private application scenarios (family usage, corporate fleet, logistic vehicles, car-sharing).

In 2009, as a decisive move in promoting local EV adoption, the national government launched the ‘Ten cities, thousand vehicles’ programme (Ministry of Finance, 2009), which had been expanded to 25 cities by August 2010. In 2010, measures providing purchase subsidies for private passenger cars were also announced (Ministry of Finance, 2010). In 2012, the State Council released the ‘Energy-saving and New Energy Automotive Industry Development Programme (2012–2020)’, which included supporting policies such as purchase subsidies, technical requirements for EV such as energy consumption efficiency, and directives for the promotion of charging infrastructure, as well as set a target of five million cumulative sales of EVs by 2020 (State Council, 2012). This has become the foundation of the Chinese government’s industrial policy for the next decade.

The central and local governments have different roles in the policy implementation: the central government’s role was to provide national purchase subsidies and guidance on technological and emission standards; local governments’ role was to provide local purchase subsidies, fund the charging infrastructure and manage local implementation (Gomes et al., 2023). In particular regarding managing local implementation, each local government has certain autonomy in deciding the concrete measures of incentives and their extent. In addition to the national purchase subsidy granted by the central government to a legitimate EV model, a local government could provide another purchase subsidy at no more than 60% of the national one. To further promote EV sales, local governments also offer many practical advantages to EV owners, such as priority registrations, unlimited road access, charging fee incentives, parking fee incentives, and highway tolls exemption. Related research shows that these practical advantages have been important drivers for EV purchase in major Chinese cities, as many of them have very limited new plate release and travel restrictions on traditional internal combustion engine cars, and incentives on charging and parking have a long-term positive impact on EV sales (He et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2023; Zhang, 2024).

An adequate charging infrastructure is a key barrier for the fast adoption of EVs. Ever since the beginning, the promotion of charging infrastructure has been highly strengthened in the EV industrial policies in China. The national directive released in 2016 announced that one city can apply for up to 120 million RMB in funding for charging infrastructure construction. In the policy implementation, many provinces and municipalities have adopted their own measures to provide incentives for building and operating charging points locally. For example, in March 2020, the city of Guangzhou announced its subsidy funding measures for EV charging infrastructure as follows: 1) charging infrastructure construction: for DC charging piles, AC-DC integrated charging piles and wireless charging facilities, a subsidy of 300 RMB/kilowatt is calculated based on the project size; for AC charging piles, the subsidy standard is 60 RMB/kilowatt; for battery swap facility, the subsidy standard is 2,000 RMB/kilowatt; 2) charging infrastructure operating: for dedicated and public charging facilities, a subsidy of 0.1 RMB/kWh is provided, within a maximum number of hours (2000 hours/year for charging stations and 3000 hours/year for battery swap stations). By the end of 2022, China has built over 5 million charging stations, reaching a EV-charging ratio at 2.5:1. And the number is growing even faster since 2023. Data published by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in July 2023 indicated that by the end of June 2023, the cumulative charging stations in China reached 6.6 million.

For the OEMs, the most important policy is the technical requirements to legitimate a NEV model for the direct financial subsidies. The central government has continued to raise the standard of technical requirements: they were extended from the simple driving range at the beginning to now including also battery efficiency measurement, vehicle energy consumption level, charging standards, etc. Based on technical requirements, every year there is a public catalogue of NEV models qualified for the direct purchase subsidies. When consumers purchase a subsidised model, they will be refunded a certain amount of the invoice depending on the model’s technical features (there is a specific calculation formula). NEVs models not satisfying the technical requirements are not listed in the catalogue thus not legitimate to receive direct subsidies. By designing and monitoring the technical aspects of the major EV models, the Chinese government has provided incentives for EV makers to constantly improve their manufacturing technology and efficiency.

China has invested a lot of financial resources to accelerate the take-off of the domestic EV market. It’s estimated that, from 2009 to 2021, the cumulative purchase subsidies for NEVs (new energy vehicles, including electric vehicles and fuel-cell vehicles) from the central and local governments amounted to approximately 200 to 250 billion RMB (Zhang, 2023). To further provide financial incentives for purchasing NEVs, the Chinese government has adopted several tax exemption policies: from the beginning, there was no car consumption tax on NEVs; since 2012, battery EVs (BEVs) are no more subject to annual vehicle and vessel tax; since September 2014, vehicle purchase tax has also been exempted for NEVs. From January 2012 to June 2023, the cumulative vehicle and vessel tax exemptions for NEVs reached 10 billion RMB; from September 2014 to June 2023, the cumulative purchase tax exemptions on NEVs exceeded 260 billion RMB, of which almost 50 billion RMB happened in the first half of 2023 (China Daily, 2023).

Purchase subsidies and tax exemptions have certainly been important drivers for the Chinese consumers to switch to the electrified mobility. The favourable financial and market conditions have allowed the Chinese EV makers to fast scale up their production capacity, multiple new EV models and reduce significantly the EV prices. With the maturating of the domestic EV market and the increasing competitiveness of Chinese EV brands, the Chinese government has started to change the policy measures, from direct financial subsidies to more market-driven mechanisms. The year of 2016 marked the beginning of the phasing-out of EV purchase subsidies from the central government; from 1 January 2023, no more purchase subsidies will be granted by the central government. Yet, local governments still have the right to provide a certain amount of purchase subsidies. In the same time, the tax exemptions are prolonged to at least 2027.

A more important evolution of the EV policy is to substitute the direct financial subsidies with a market-based NEV credit system; together with the pre-existing fuel consumption requirements, known as corporate average fuel consumption (CAFC), they form the so-called ‘dual credits management system’. The ‘New Energy Vehicle Mandate’ that came into force on April 1, 2018 imposed NEV credit targets as 10% of the conventional passenger vehicle market in 2019 for any carmaker with over 30,000 vehicles manufactured locally or imported yearly in China (gradually increasing to 12%, 14%, 16% and 18% in 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023). The NEV credit, in the case of BEV, is calculated based on driving range, energy density coefficient and power consumption coefficient, with a limit of maximum points. The CAFC is calculated based on vehicle kerb mass: a company can earn credits if its current annual CAFC is lower than the CAFC target; its design is learnt from California’s zero-emission vehicle regulations. The first phase of China’s CAFC standard started in 2005 with a series of regulations to improve vehicle fuel efficiency. For the current phase 5 (2021–2025), the target is 4.0 L/100 km. This way, the government will no longer bear the financial burden; instead, OEMs will have to invest in R&D to improve the fuel efficiency of their vehicles or buy credits from other OEMs to avoid penalties if the CAFC and NEV credit targets are not met.

From the perspective of policy mechanism, the dual credit management system is an institutional attempt to establish a market-oriented mechanism for the coordinated development of energy-saving and NEVs. Since its implementation in 2018, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), together with the four departments, has organised five credit transactions, with a cumulative transaction amount of more than 25 billion RMB. The dual credit management system has also gone through several adjustments, as the Chinese NEV market has gradually shifted from policy-driven to market-driven, with more and more consumers actively switching from traditional fuel vehicles to NEVs.

A very good example of how the Chinese government tailors an explicit industrial policy to support the growth of the national EV industry is the measure of ‘whitelist’ for battery makers. The leading Chinese EV battery firms are now among the largest producers in the world; but it did take time for them to grow big and competitive, able to challenge their Japanese and South Korean peers. Back in 2016, to exclude foreign competitors and protect its nascent lithium-ion battery industry, the MIIT introduced the catalogue of ‘Regulations on the Standards of Automotive Power Battery Industry’ (commonly known as the ‘whitelist’). Only battery models fully owned by domestic battery makers were listed, and hence eligible for government NEV subsidies. This measure temporally chased Japanese and South Korean battery firms out of the Chinese local market and gave Chinese firms a time window to build their own comparative advantages (Wang et al., 2022). With the Chinese EV battery sector becoming technologically and economically competitive, and also starting to face overcapacity issue, the Chinese government has reopened the domestic market in 2018, inviting market forces to drive the industrial consolidation. Although disputable as a protectionist measure, this episode is a perfect demonstration of the dynamic way of policy making in China.

In 2020, the central government has further strengthened the crucial role and a continued support of the auto industry by publishing its guidelines in the “New energy vehicle industry development plan (2021-2035)”. The 2021-2035 Plan proposes that by 2025, the average power consumption of new pure electric passenger cars will be reduced to 12.0 kWh/100 kilometres, the sales of NEVs will reach about 20% of the total new car sales (which was already achieved in 2022), and highly autonomous vehicles will be implemented in limited areas and in specific scenarios for commercial applications. By 2035, pure electric vehicles will become the mainstream of new sales; public sector vehicles will be fully electrified; fuel cell vehicles will be commercialized; and highly autonomous vehicles will be applied on a large scale, effectively promoting energy conservation, emission reduction, and social operation efficiency.

Conclusion: EV industry at frontier of multiple transitions

The transition from traditional transport towards low-or zero-emission modes of transport cannot be left to technological roadmaps and market coordination alone, but depends on a more comprehensive policy to steer the electrification of the automotive industry on to a greener, more efficient and socially inclusive track (Pardi, 2021). We see that the EV industrial policies in China have gone through several phases, showing important changes and evolutions, with the goal to not only reinforce China’s leadership in the emerging global EV industry but also accelerate the decarbonisation of its economy.

Under the support of a comprehensive package of industrial policies, a dynamic and competitive domestic EV industry has formed and become the basis for the future development of sustainable and intelligent mobility in China. In the same time, the industrial supply chain of EV industry is extremely long and complex; the Chinese government continues to design, monitor and adjust related policies, such as regarding the upstream raw material supply or the downstream end-of-life vehicle treatment and battery recycling. In particular, with the increasingly stringent global requirement on low-emission standard and carbon footprint certificate, the whole automobile industry must reform its growth strategy. The EV industry is just at the frontier of multiple transitions which advocate for renewable energy sources, sustainable, circular and shared economy models, and smarter management platforms and systems. To make these transitions smooth and effective, relevant industrial policies will become even more important and need to take into consideration more stakeholders and full impact.

Bibliography

CAAM, China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, http://en.caam.org.cn/

China Daily (2023). In the first half of the year, 49.17 billion yuan in new energy vehicle purchase taxes were exempted nationwide (author’s translation from Chinese). China Daily Overseas Edition, 2 August 2023, available at: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202308/content_6896093.htm, retrieved on 17 January 2024.

Gomes, A. P., Pauls, R., ten Brink, T. (2023). Industrial policy and the creation of the electric vehicles market in China: demand structure, sectoral complementarities, and policy coordination. Cambridge Journal of Economics, Volume 47, Issue 1, January 2023, pp. 45-66, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beac056.

Gong, H., Wang, M. Q. and Wang, H. (2013). New energy vehicles in China: policies, demonstration, and progress. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, vol. 18, no. 2, 207-28.

He, H., Jin, L., Cui, H., Zhou, H. (2018). Assessment of electric car promotion policies in Chinese cities. International Council on Clean Transportation. pp. 1-60.

Liu, Y., Zhao, X., Lu, D., Li, X. (2023). Impact of policy incentives on the adoption of electric vehicle in China. Transportation research part A: policy and practice, Vol. 176:103801.

Ministry of Finance (2009). Notice on carrying out the pilot work of demonstration and promotion of energy-saving and New Energy Vehicles [关于开展节能与新能源汽车示范推广试点工作的通知]. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-02/05/content_1222338.htm, retrieved on 16 January 2024.

Ministry of Finance (2010). Notice on launching the pilot program of subsidies for private purchase of new energy vehicles [关于开展私人购买新能源汽车补贴试点的通知]. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2010-06/04/content_1620735.htm, retrieve on 16 January 2024.

O’Donovan, A. (2024). Electrified Transport Market Outlook 4Q 2023: Growth Ahead. BloombergNEF, January 4, 2024.

Pardi, T. (2021). Prospects and contradictions of the electrification of the European automotive industry: the role of European Union policy. International Journal of Automobile Technology and Management, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 162-179.

Qian, Y. (2002). How reform worked in China. William Davidson Working Paper Number 473, June 2002. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.317460, retrieved on 15 January 2024.

Roland, G. (2000). Transition and economics: Politics, markets, and firms. MIT press.

State Council (2012). State Council’s notice on energy-saving and New Energy Vehicles industry development plan (2012-2020) [国务院关于印发节能与新能源汽车产业发展规划(2012―2020年)的通知]. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2012-07/09/content_2179032.htm, retrieved on 16 January 2024.

State Council (2021). State Council’s Notice on issuing the New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan (2021-2035) [国务院办公厅印发《新能源汽车产业发展规划(2021-2035年)的通知]. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-11/02/content_5556716.htm, retrieved on 18 January 2024.

Wang, X., Zhao, W., Ruet, J. (2022). Specialised vertical integration: the value-chain strategy of EV lithium-ion battery firms in China. International Journal of Automobile Technology and Management, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 178-201.

Wang, S., Yang, D. Y. (2023). Policy Experimentation in China: The Political Economy of Policy Learning. NBER Working Paper Series, available at: http://davidyyang.com/pdfs/experimentation_draft.pdf, retrieved on 10 January 2024.

Zhang, R. (2023). Countervailing subsidies cannot stop China’s electric vehicles from going overseas” (author’s translation from Chinese). Securities Times Network, 24 October 2023, available at: https://www.stcn.com/article/detail/1012414.html, retrieved on 17 January 2024.

Zhang, T., Burke, P. J., Wang, Q. (2024). Effectiveness of electric vehicle subsidies in China: A three-dimensional panel study. Resource and Energy Economics, Volume 76, February 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2023.101424.