By Alessia A. Amighini[1]

Global Value Chains (GVC) have been massively shaped by participation of emerging economies. Emerging economies’ participation in GVC is one of the most outstanding developments in the global economy since the mid-1990s. Until the 1980s, North-North trade dominated global trade flows. Then, South-North trade and South-South trade have risen sharply.

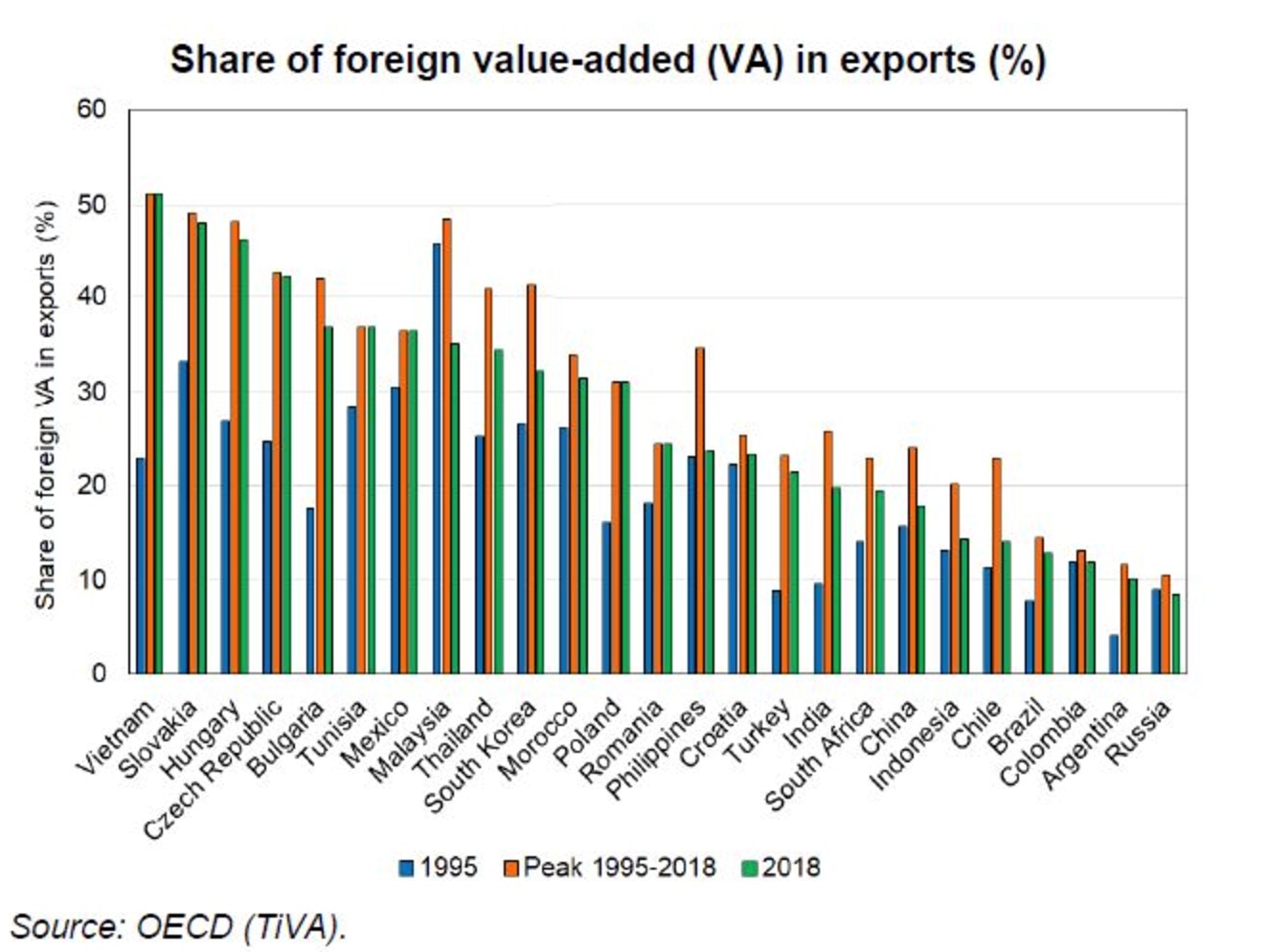

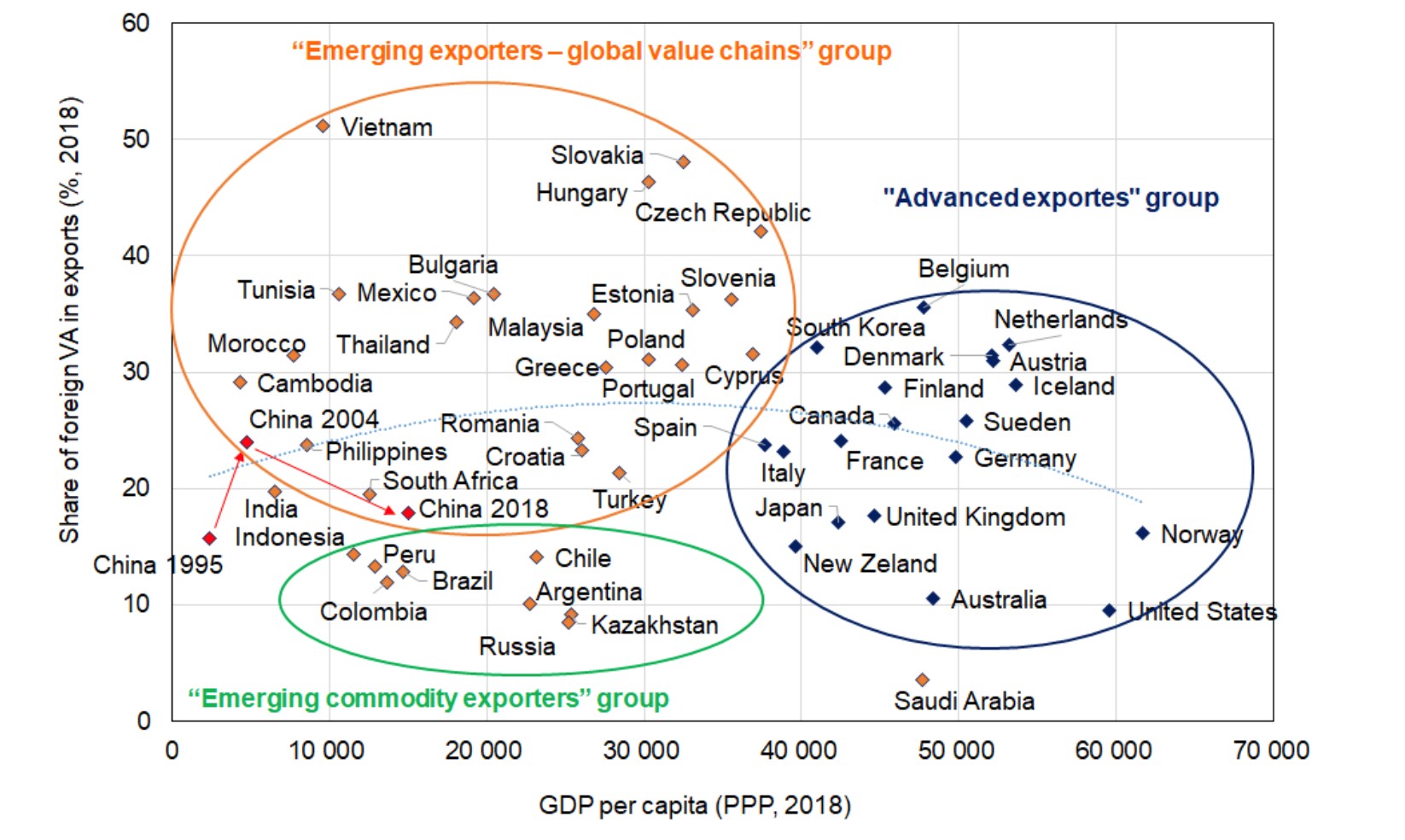

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is clearly at the centre of this trade growth: its share of global exports increased sixfold in the span of 40 years (now 14% of global, making it the world's top exporter). Besides China, other countries benefited from the massive relocation of production activities from the North: most notably, Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand in Southeast Asia, Slovakia, Hungary, Czech Republic and Bulgaria in Eastern Europe, Tunisia and Morocco in North Africa. These countries engaged mostly in so-called backward participation, i.e. the share of foreign value added in their exports. Overall, the North’s declining share of global exports, down from 80% in 1991 to 60% in 2018, mirrors the South’s share of global exports up from 20% to 40% over the same period. This trend faced a significant halt in 2018, when a withdrawal from free trade started in the United States, with the introduction of tariffs on imports from China. This contributed to reduce not only US imports from China, but also the ability of other countries to continue exporting, being engaged in China-led regional value chains, as in the case of Malaysia.

Other emerging economies with important shares in GVC, like Vietnam, did not experience severe decline in GVC participation, instead they actually maintained their share of foreign value added in exports. Vietnam in fact partly replaced Chinese exports to the United States.

Moreover, the current trade circumstances – namely the ongoing trade war between the United States and China – which clearly reduced the potential for further participation of emerging exporters in GVC, there is also a general trend to be considered. There seems to be a ‘natural’ decline in backward GVC participation as the GDP per capita increases. This is what stands out from comparing emerging exporters to advanced exporters. There seems to be a negative correlation between trade integration and level of development, which is likely to be due to the higher production capabilities of advanced economies, and therefore higher domestic value added in their exports compared to foreign value added.

This suggests that the halt in GVC participation due to the beginning of trade frictions between the United States and China in 2018 might have anticipated a trend that we should have expected in any case. In the absence of their role in GVCs, some emerging economies may face a decline in growth before developing domestic production capabilities beyond mere assembly or simple processing. There is an increasing uncertainty in international trade relations during the second presidential mandate for President Trump – who already announced some peculiar ideas that could lead to an unprecedented agreement between the United States and China for a target amount of US exports to China. This further adds to the specific uncertainty faced by emerging economies regarding their future role in the global economy.

[1] Associated Professor of Economics at the Department of Economic and Business Studies at the University of Piemonte Orientale, member of OEET at CCA as well as Co-Head of Asia Centre and Senior Associate Research Fellow at ISPI