By Sara Balestri, Andrea Crippa, Luca Pieroni[1]

Recent years have witnessed a marked slowdown in global progress in reducing hunger and malnutrition, with food insecurity remaining persistently high, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (FAO, IFAD et al., 2024). In this region, households are frequently exposed to overlapping and reinforcing shocks, including climate-related events, economic instability, and demographic pressures (Barrett, 2021). Among these, droughts are especially relevant for low-income, agriculture-dependent economies, as they affect food security not only by reducing food availability, but also by constraining incomes, disrupting markets, and weakening purchasing power (Myers et al., 2017; IPCC, 2023). Understanding how household food security evolves over time in response to such shocks therefore remains a central empirical challenge.

Much of the existing literature has relied on static measures of food security, often focusing on caloric intake or food availability, while paying less attention to diet quality, dietary diversity, and intra-household dimensions (Costlow et al., 2025). Moreover, empirical analyses are frequently constrained by limited longitudinal data and by econometric approaches that rely exclusively on observed indicators, potentially overlooking the multidimensional and partly unobservable nature of food security (Hangoma et al., 2024; Izraelov and Silber, 2019). These limitations raise concerns about measurement error, omitted variables, and the ability to capture persistence and mobility in food security status over time (Ahmadzai et al., 2025).

Against this background, this study examines the dynamics of household food security in Sub-Saharan Africa by focusing on dietary diversity and on transitions across different food security conditions in response to climate shocks. The analysis draws on panel data from the Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) for Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda, covering four survey waves between 2010 and 2020 and comprising 25,502 household observations. Household food security is proxied by the Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS), a widely used indicator that reflects both the quality and quantity of food consumption through the number of food groups consumed in the previous 24 hours (Swindale and Bilinsky, 2006). Following Vaitla et al. (2017), the continuous HDDS is recoded into four ordered categories, ranging from scarce to plentiful dietary diversity, to facilitate interpretation while preserving meaningful variation in diet quality.

To account for the dynamic and multidimensional nature of food security, the empirical strategy adopts a latent variable framework based on a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) (Bartolucci, 2017). In this setting, household food security is conceptualized as an unobservable state that evolves over time, while the observed HDDS categories provide imperfect signals of that state. The model jointly estimates the probability of households starting in a given latent food security condition and the probability of transitioning between conditions across survey waves. By explicitly modelling unobserved states, this approach helps to address some of the limitations of classical econometric analyses based solely on observed outcomes, including measurement error and unobserved heterogeneity. At the same time, the inclusion of observable covariates—such as age and gender of the household head, exposure to drought shocks, and distance from urban centres—in both initial and transition probabilities makes the latent variable approach complementary to standard analyses of determinants rather than a substitute for them.

Model selection based on information criteria supports the identification of three latent food security states, which can be interpreted as a scarce variety diet (food insecure), a middle variety diet (somewhat secure), and a plentiful variety diet (food secure). The estimated conditional response probabilities reveal a strong correspondence between these latent states and the observed HDDS categories, lending substantive meaning to the classification. Most households assigned to the scarce variety diet state report low or middle-scarce dietary diversity, whereas households in the plentiful variety diet state are much more likely to exhibit high dietary diversity.

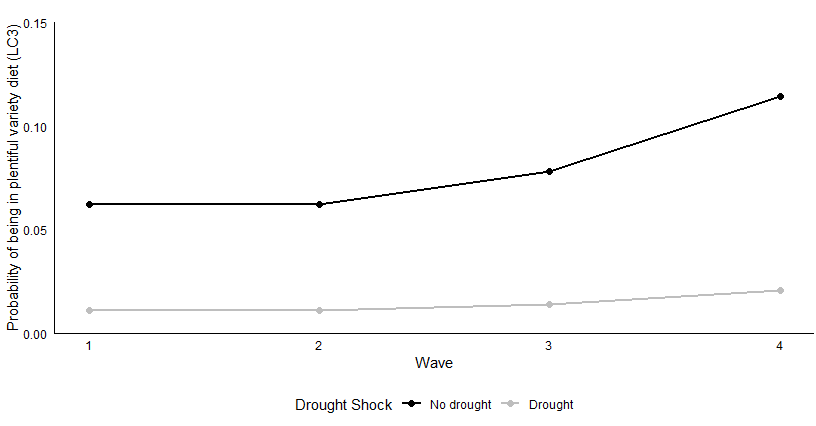

The estimated transition dynamics point to the relevance of both demographic characteristics and environmental conditions. Older household heads display a slightly higher probability of transitioning towards the most food-secure state, while female-headed households face a substantially lower likelihood of moving to a plentiful variety diet. Greater distance from urban centres is also associated with a reduced probability of reaching high dietary diversity, consistent with constraints related to market access and food availability. Drought shocks emerge as a particularly important factor: exposure to drought markedly reduces the probability of transitioning from a scarce variety diet to a plentiful variety diet, indicating that climate-related shocks can hinder improvements in diet quality over time. These effects are identified within a dynamic framework that accounts for state dependence, highlighting how shocks influence not only current outcomes but also future food security trajectories.

Figure 1 illustrates the estimated impact of drought on the likelihood of households being in the plentiful variety diet latent state over time. The figure shows that households affected by drought consistently exhibit a lower probability of being in, or moving into, the most food-secure state compared to non-affected households. This graphical evidence complements the regression-based results and underscores the role of climate shocks in shaping initial dietary conditions and subsequent transitions.

Figure 1: Effect of Drought on the Probability of Being in a Plentiful Variety Diet

Overall, the analysis provides evidence that household food security in Sub-Saharan Africa is characterized by marked persistence and non-negligible mobility across dietary diversity conditions over time. The results suggest that demographic characteristics and spatial factors are systematically associated with households’ ability to reach and maintain more diversified diets, while climate-related shocks, such as droughts, substantially hinder improvements in dietary outcomes. By focusing on dietary diversity and on transitions between different food security states, the findings offer a nuanced picture of vulnerability and resilience in the presence of environmental stressors.

References

Ahmadzai, H., & Morrissey, O. (2025). Climate shocks, household food security and welfare in Afghanistan. Food Policy, 134, 102910.

Barrett, C. B. (2021). Overcoming global food security challenges through science and solidarity. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 103(2), 422-447.

Bartolucci, F. (2017). Editorial: Special section on latent variable models for longitudinal data. Biometrical Journal, 59(4), 781–782. DOI: 10.1002/bimj.201700041.

Costlow, L., Herforth, A., Sulser, T. B., Cenacchi, N., and Masters, W. A. (2025). Global analysis reveals persistent shortfalls and regional differences in availability of foods needed for health. Global Food Security, 44, 100825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2024.100825.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO. (2024). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2024: Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. Rome: FAO.

Hangoma, P., Hachhethu, K., Passeri, S., Norheim, O. F., Rivers, J., & Mæstad, O. (2024). Short- and long-term food insecurity and policy responses in pandemics: Panel data evidence from COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries. World Development, Elsevier, vol. 175(C).

IPCC. (2023). Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Summary for Policymakers). IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland.

Izraelov, M., & Silber, J. (2019). An assessment of the global food security index. Food Security: The Science, Sociology and Economics of Food Production and Access to Food, Springer. The International Society for Plant Pathology, 11(5), 1135-1152, October.

Myers S. S., Smith M. R., Guth S., Golden C. D., Vaitla B., Mueller N.D., Dangour A.D., and Huybers P. (2017). Climate Change and Global Food Systems: Potential Impacts on Food Security and Undernutrition. Annual Review of Public Health, March 20(38), 259-277.

Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P. (2006) Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, Washington DC.

Vaitla, B., Coates, J., Glaeser, L., Hillbruner, C., Biswal, P., & Maxwell, D. (2017). The measurement of household food security: Correlation and latent variable analysis of alternative indicators in a large multi-country dataset. Food Policy, Elsevier, 68(C), 193-205.

[1] University of Perugia, Italy.