By Stefano Schiavo[1]

The globalization of agriculture has intensified significantly over the past four decades, marked by a six-fold increase in trade in agricultural goods. As a result, approximately 25% of global agricultural production is currently exported (D’Odorico et al. 2014) and food imports feed between 2 and 3 billion people (MacDonald et al. 2015).

While trade offers benefits such as risk diversification and the ability to decouple population growth from local resource availability, it simultaneously increases countries' exposure to shocks originating elsewhere and fosters dependence on other nations.

These competing effects can be investigated using network-based simulations that study diffusion of global or local shocks affecting agricultural production (Grassia et al. 2022). Since three main staples --corn, rice and wheat-- account for more than 50% of global caloric intake, these commodities represent a natural starting point for the analysis.

The network model simulates shock diffusion by tracking key steps: a production shock causes a global price increase, which reduces import demand. If the shock is not fully compensated, countries reduce exports to meet domestic needs, propagating the shortage across the network. Countries use up to 50% of their existing reserves to compensate for shortfalls. Finally, any remaining demand deficit is absorbed via a reduction in consumption, allowing the ultimate impact on caloric intake and food security to be computed.

Two scenarios are simulated, both caused by extreme weather events: a severe localized shock and a system-wide disturbance. The first replicates the major draught that hit the US in the 1930s (aka Dust Bowl) and would result in substantial production losses in American agricultural production: -40% for corn, -30% for wheat, and -20% for rice (Glotter and Elliot, 2016). The second scenario involves a simultaneously production declines across multiple regions (Lloyd’s 2015), leading to a significant fall in global food supply: -10% for Corn and -7% for both Wheat and Rice.

In both cases, the shocks propagate globally, affecting even counties that do not directly import from producers directly hit by extreme weather events, and countries located very far from the epicenters of the crises. The number of countries facing a severe caloric deficit (above 250 kcal/day/per capita) ranges between 13 (Dust Bowl scenario) and 36 (Global shock scenario), generating an important increase in the number of people suffering from malnutrition. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that the number of undernourished people would increase by 32 to 130 million globally, depending on the specific scenario.

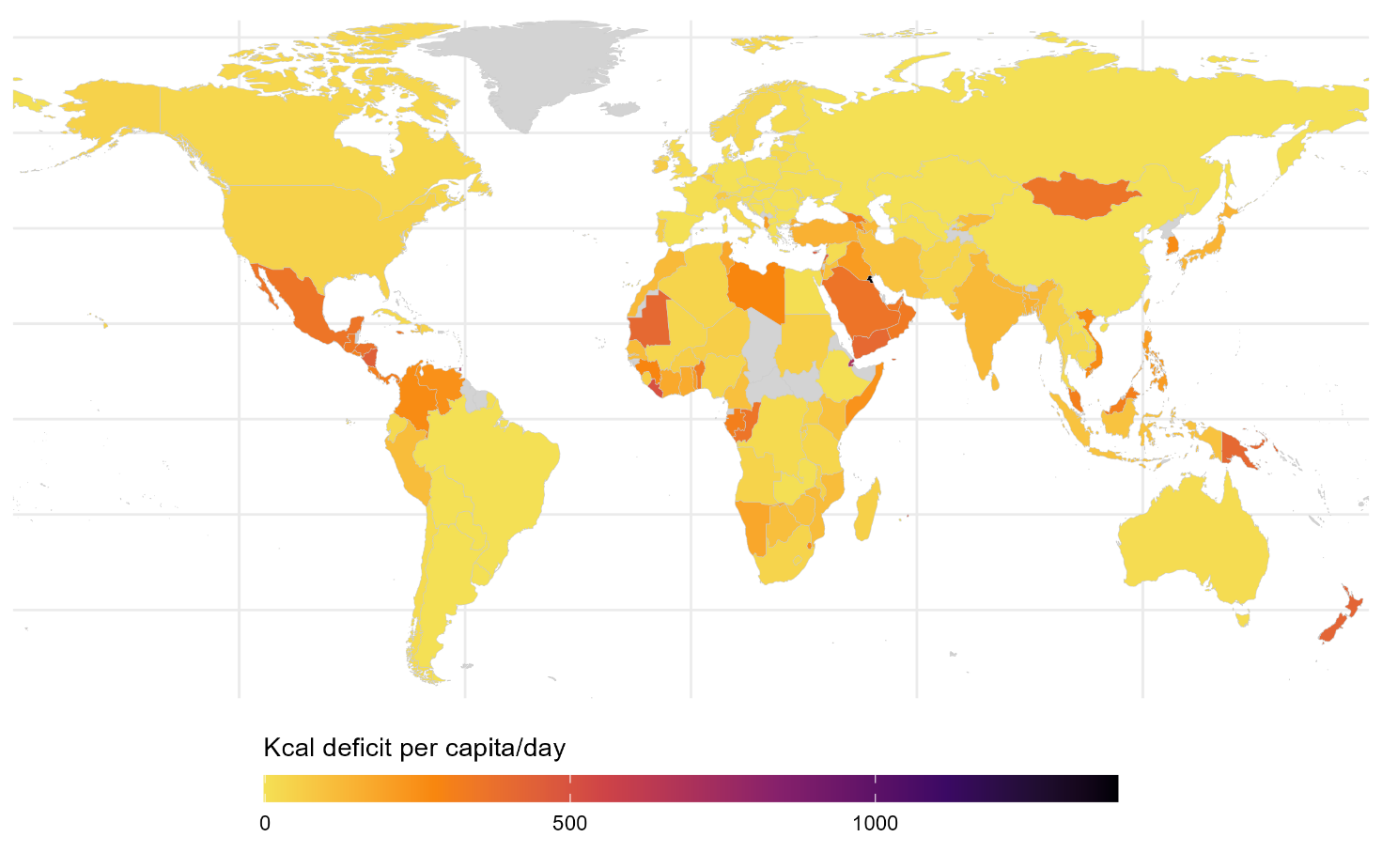

Figure 1 – Combined caloric deficit as a result of a global shock to corn, rice and wheat production. Own calculations based on simulation results.

The shocks cause major structural changes in the trade networks, with 30% to 55% of trade links being severed and the number of exporting countries falling by 30% to 60%. At the same time, the system shows a remarkable degree of resilience, as only a handful of countries are completely cutoff from trade. Clearly, the effects are not homogeneous across the world (see Figure 1). On average, countries that are heavily dependent on food imports, especially from producers directly hit by the shocks, face higher caloric deficits. On the other hand, large stocks of reserves help coping with the disruptions and import diversification also acts as an important buffer.

Additional insights emerge from the comparison of the baseline model setup with a “non-cooperative” setting in which countries do not share their reserve stocks, that is, they restrict exports before deploying their reserves and thus only use food stocks to stabilize internal demand, not world markets. The simulation show that non-cooperative behaviour significantly exacerbates global suffering, increasing the average caloric deficit, the number of countries with a significant decline in food availability, and the number of additional undernourished people. This outcome underscores that international cooperation remains an important tool for mitigating the impact of shocks to agricultural production, and for preventing catastrophic humanitarian outcomes during a food crisis.

References

D’Odorico, P., Carr, J. A., Laio, F., Ridolfi, L. and Vandoni, S. (2014), Feeding humanity through global food trade, Earth’s Future 2(9), 458–469.

Glotter, M. and Elliott, J. (2016), Simulating US agriculture in a modern Dust Bowl drought, Nature Plants 3(1), 1–6.

Grassia, M., Mangioni, G., Schiavo, S. and Traverso, S. (2022), Insights into countries’ exposure and vulnerability to food trade shocks from network‑based simulations, Scientific Reports 12: 4644.

Lloyd’s (2015) Food System Shock. The insurance impacts of acute disruption to global food supply, Emerging Risk Report 2015.

MacDonald, G. K., Brauman, K. A., Sun, S., Carlson, K. M., Cassidy, E. S., Gerber, J. S. and West, P. C. (2015), Rethinking agricultural trade relationships in an era of globalization, BioScience 65(3), 75–289.

[1] University of Trento, Italy.

This piece summarizes results from work with Emile van Ommeren (University of Trento), Giuseppe Mangioni and Marco Grassia (University of Catania). It is based on the project “Food Connections. Intended and unintended consequences of trade on food and nutrition security”, funded by the European Union Next generation EU, mission 4, component 2 (CUP E53D23016430001 – Project code P202233ZTR).