by Giorgia Giovannetti[†] and Arianna Vivoli[‡]

This article intends to contribute to the debate exploiting cross-country national representative surveys on the impact of the pandemic conducted by the World Bank Enterprises Surveys. On a sample of firms from 18 countries, including emerging economies, with a before-and-after analysis, we find that international firms have been less impacted by the pandemic with respect to their domestic counterparts. Secondly, unpacking the different ways through which firms can operate in the international market, we find that both the import and the export channel shield firms from the shock, but with no statistically significant difference between the two, while being part of a GVC (a status proxied by being a trader with an internationally recognized high-quality certification) makes the difference. Lastly, international firms are more likely to adapt their business strategies (e.g., starting or increasing business online activities and remote working) to the changing situation and substantially less likely to reduce their temporary workforce.

Covid-19 pandemic has changed the world we live in, with effects that are going to shape the future of our societies. Economy has been severely hit due to pervasive lockdown measures and disruptions of international supply chains. The pandemic-induced supply and demand shocks, whose magnitude is unprecedented, had disruptive effects on the globalized production process. Nonetheless, already before the Covid-19 outbreak, since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008, GVCs and international trade in general were indeed experiencing a slowdown (Antràs, 2020; World Bank, 2020). Other than the recession, several game-changer forces have been playing a fundamental role. First, as maintained by Antràs, (2020), the pace of technological progress, that was one of the keys of the hyper-globalization take-off, remains high but has slowed down compared to the levels reached in the 1980s and 1990s. Second, the advent of new technologies like automation, robotics and 3D printing, might have controversial effects on GVC participation, both negatively (via facilitating re-shoring of firms to high-income countries), as in Rodrik (2018) and positively (via increasing productivity of high-income countries’ firms, increasing in turn their demand for intermediate inputs from low-income countries), as in Artuc et al. (2018). Third, political and social turmoil such as the US-China trade war (Bellora and Fontagnè, 2020) or Brexit have also played a role in the slowing down of globalization. Fourth, the economic development induced by GVCs integration of labour-intensive countries, China overall, eroded the wage differentials that made profitable the development of GVCs in the last decades. For all the reasons, and also because we are not over the pandemic yet, trying to disentangle the effect of Covid-19 on the international production process is not straightforward and the debate is very animated.

This article intends to contribute to the debate exploiting cross-country national representative surveys on the impact of the pandemic conducted by the World Bank Enterprises Surveys. On a sample of 9,555 firms from 18 countries, with a before-and-after analysis, we find that international firms have been less impacted by the pandemic with respect to their domestic counterparts. Secondly, unpacking the different ways through which firms can operate in the international market, we find that both the import and the export channel shield firms from the shock, but with no statistically significant difference between the two, while being part of a GVC (a status proxied by being a trader with an internationally recognized high-quality certification) makes the difference. Lastly, international firms are more likely to adapt their business strategies (e.g., starting or increasing business online activities and remote working) to the changing situation and substantially less likely to reduce their temporary workforce.

Related empirical literature

Empirically, at the country level, a rapidly growing literature has provided heterogeneous results on whether more integrated countries have been more impacted by the Covid-19 shock; for instance, Bonadio et al., (2020) through a simulation analysis find that actually, one-third of the total Covid-19-induced GDP contractions comes from the transmission of the foreign lockdowns[1]. Similarly, Berthou and Stumpner (2022) finds that country-sector pairs more integrated into the international market suffered more from the pandemic-induced lockdown measures. Conversely, Giglioli et al., (2021) document that countries more integrated into international production suffered lower GDP losses, especially the “upstream” inputs supplying countries, and that, especially in the second wave (from October 2020 to January 2021), they experienced a more pronounced rebound relative to less integrated countries.

At the sectoral level, Giovannetti et al., (2020) show that, with respect to the GFC, this time GVCs have contributed less to the transmission of the shock (also because, differently from the 2008 financial crisis which had impacted the manufacturing sectors, the pandemic has hit harder services, or in general sectors less integrated in the international market and that needed a face to face interaction). With the same data source that we use, but with a sector-level gravity model, Espitia et al., (2021) find that sectors that faster adopted remote working contracted less during the pandemic. Moreover, they find that operating in GVCs increased firms’ vulnerability to shocks suffered by trading partners, but at the same time, it also reduced their vulnerability to domestic shocks.

At the firm level, the evidence is scarce but growing; for instance, Giglioli et al. (2021) find that international Italian firms experienced lower reductions in sales compared to their domestic counterparts, especially during the second wave of the pandemic. de Lucio et al. (2022), using Spanish firm-level data, find that among firms operating in the manufacturing sector, the negative effect of the pandemic was lower if firms participated in GVCs. Building on a cross-country analysis, Borino et al., (2020) find instead that international firms are affected by the Covid-19 crisis more than domestic firms due to their exposure to both domestic and foreign lockdowns; at the same time though, they are less likely to lay off workers and file for bankruptcy and are more likely to adopt countermeasures that continue production such as telework and work from home.

Data and descriptives

The data used in this study come from the World Bank Enterprise Surveys (WBES) project. From the standard WBES, we use information on firm characteristics as firm performances, employment and international status, for firms operating in the non-agricultural, non-extractive private sectors. As for the information on the impact of Covid-19, we extract information from ad hoc designed waves of WBES - the Follow-up. These waves include all the enterprises interviewed in the last available standard Enterprise Survey and report detailed information on firms’ response to Covid-19 such as the impact on sales and workforce, and change in business strategies (e.g., business online, remote working, changes in production). Using the common firm identifier, we can merge pre- and post-Covid-19 survey waves to link pre-Covid-19 firms’ characteristics with post-Covid-19 response to the shock. To our knowledge, this is one of the very first open access, cross-country, firm-level dataset that offers the opportunity to investigate the impact of the pandemic on the private sector for different countries. Our final sample comprises 9,555 firms from 18 countries[2].

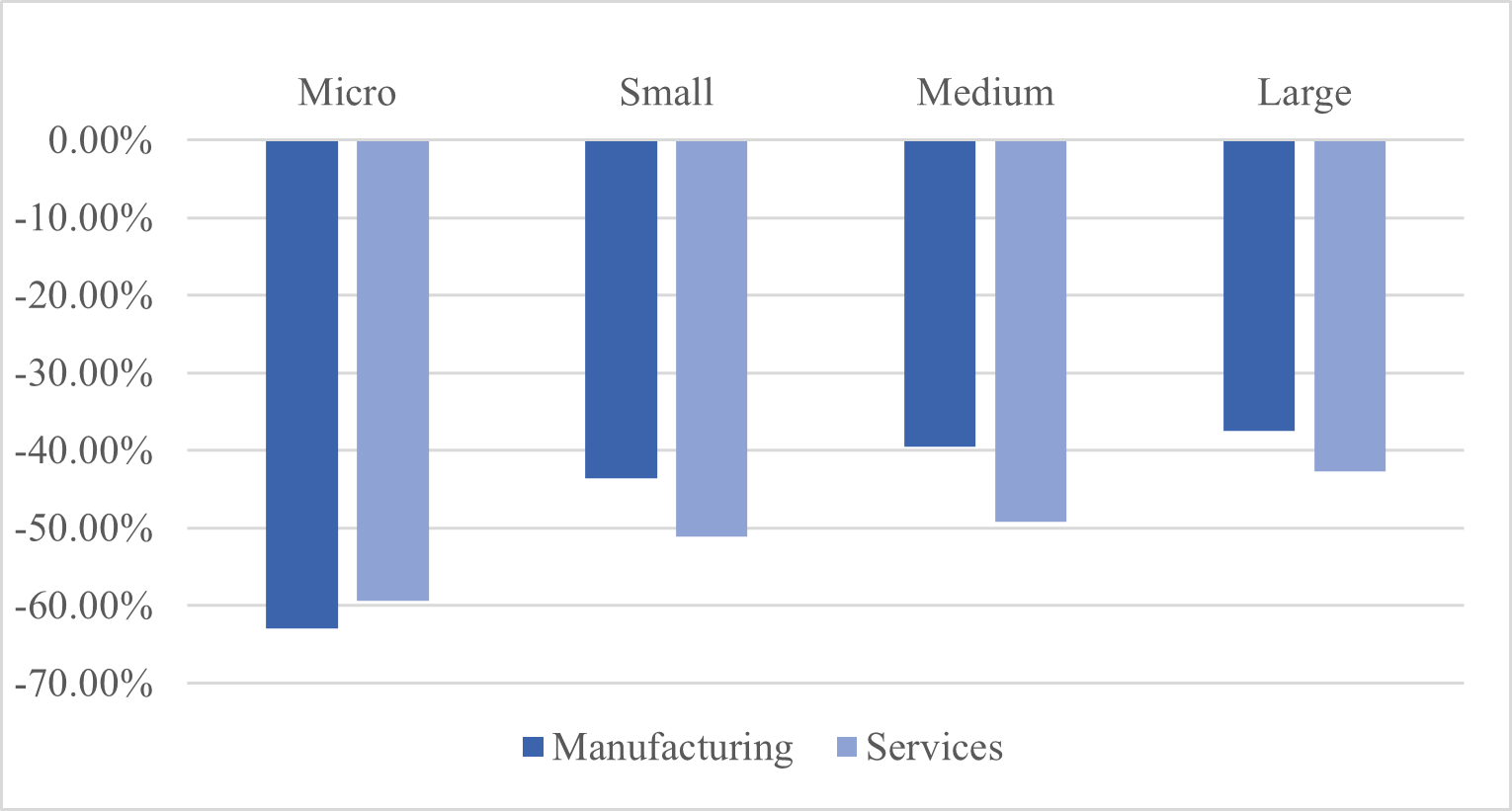

As for the impact of the pandemic, the shock was pervasive. All countries included in our sample have experienced catastrophic reductions in sales, with the mean reduction in sales around -45.05%. Interestingly, the pandemic seems to have hit harder lower-middle income countries with respect to other income groups: the average change in sales for this subset of countries is -45.19%, compared to a -34.90% for upper-middle income countries and -18.97% for high income countries (an evidence in line with Karalashvili and Viganola, (2021) and with Olczyk and Kuc-Czarnecka, (2021)). Moreover, from Figure 1, we can see how differently from the GFC (and in line with Giovannetti et al., 2020), the Covid-19 crises appears to have hit services– except for micro enterprises – harder than manufacturing (indeed, the sector that reports the higher losses is Hotel and Restaurants, with an average reduction of -59.38%); we can also see how much size matters: the smaller the firm’s size, the higher the losses during the pandemic.

Figure 1: Average reduction in sales by size and sector

Source: Authors’ elaboration on WBES data. Note: For firm size, we follow the World Bank categorisation: micro firms have 1-4 employees, small 5-19, medium 20-99 and large have 100+ employees.

Adopting a firm-level perspective, Table 1 presents the differences between domestic and international firms concerning pre-Covid-19 characteristics (panel A) and Covid-19 response (panel B). We define as international all the firms that either export, import or are affiliate (i.e., with at least 10% of foreign ownership). From panel A, we can see that the so-called internalization premia envisaged by the literature are respected (Antràs and Chor, 2021). Being international is associated with better performances: first, international firms are significantly larger and concentrated in the upper part of the size distribution, whereas domestic firms tend to be mostly small (with from 5 to 19 employees); secondly, international firms are also significantly more productive than domestic ones.

In panel B, we report firms’ response to the Covid-19 shock. International firms responded slightly better to the pandemic outbreak: a higher percentage of domestic firms were forced to exit the market (5.77%) than their international counterparts (3.79%) after the first wave. Looking at the percentage of firms reporting a reduction in sales, we find a small difference, not statistically significant, between domestic and international firms: overall this seems to suggest that the pandemic shock has been extremely pervasive for both domestic and international firms. However, focusing on average turnover losses, we can see that domestic firms experienced significantly higher losses (-53.11% vs. -49.49%); the same applies when we look at the percentage of domestic and international firms that experienced a reduction in sales that is bigger than their sector-country median (64.60% vs. 59.96%). Also, a higher percentage of domestic firms report to have experienced a decrease in their supply of inputs because of Covid-19, while we detect no relevant differences in the decrease of demand for firms’ products. Lastly, international firms report to have started (or increased) adaptive strategies (as business online activities and remote working) significantly more than domestic firms. Given this evidence, what we try to do next in our analysis is to unpack this “international” status, in order to try to understand from which dimensions this international premium is originated.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of the estimation sample

|

Domestic |

International |

Difference |

|

|

Panel A: Internationalization premia |

|||

|

Dimension |

|||

|

- Micro (1-4) |

2.31% |

1.45% |

-0.86** |

|

- Small (5-19) |

56.41% |

39.08% |

-17.33*** |

|

- Medium (20-99) |

28.83% |

34.48% |

5.65*** |

|

- Large (100+) |

12.46% |

24.99% |

12,53*** |

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

|

|

Total employment (ln) |

2.90 |

3.48 |

0.58*** |

|

Revenue per worker (ln) |

10.94 |

11.41 |

0.43*** |

|

Panel B: Response to Covid-19 |

|||

|

% of firms permanently closed |

5.77% |

3.79% |

-1.98%** |

|

% of firms with turnover losses |

70.66% |

69.97% |

-1,07% |

|

Average turnover losses |

-53.11% |

-49.49% |

-3.61%*** |

|

% of firms with turnover losses wrt the country-sector |

64.60% |

59.96% |

-4,64%*** |

|

% of firms decreasing supply of inputs |

61.74% |

56.42% |

-5.32%*** |

|

% of firms with decreased demand |

66.41% |

64.22% |

-2.19% |

|

% of firms adopting smart working |

23.25% |

35.07% |

11.82%*** |

|

% of firms adopting business online |

22.53% |

25.59% |

3.06%*** |

|

Total 9,555 |

3,475 |

6,080 |

Note: *, **, *** indicate when the difference in outcomes between the two groups is statistically significant respectively at 10%, 5% and 1%.

Key findings

Our results are the following: first, we differentiate the impact of internationalization between being a trader and being part of a multinational. What emerges is that the average beneficial effect of internationalization is mainly driven by traders, while being an affiliate has no (additional) impact; this holds for the manufacturing sector and for countries in the high- and upper-middle income groups, while we detect no statistical difference between international and domestic firms in services and in lower-middle income countries. This fact can be probably linked to the sectoral-specific participation to trade (indeed manufacturing firms are generally more involved in the international production than services), but also because services (especially those that require vis-à-vis interactions, e.g., tourism and restaurants) have been particularly hit by mobility restrictions and lockdown measures. We suppose that for firms in services the impact has been so devastating that not even being part of an international network has shielded firms from the shock.

Secondly, we unpack the ‘trader’ status by looking separately to the import and to the export channel. Interestingly, both being an importer and being an exporter is associated with a better performance compared to domestic firms, but we find no statistically significant differences between the two modes of internationalization. In other words, both foreign supply and demand have helped in reducing turnover losses, but we detect no relevant differences in terms of magnitude between the two mechanisms. At the same time, being part of a GVC (a status proxied by the possession of an internationally-recognized certification) substantially improves firms performance. This result may depend on the fact that, for the capital good-intensive nature of GVCs, the pandemic may have hit firms in GVCs less, because Covid-19 (and lockdown measures) hit harder industries that require face-to-face interactions, that usually are less internationalized (as in Giovannetti et al., 2020). But it can also be, as in de Lucio et al. (2022), that international trade between firms in GVCs resisted better to the pandemic outbreak, because of the stickiness of inter-firm relationships of firms in GVCs. Unfortunately, for now we cannot test this hypothesis for data availability constraints.

Lastly, international firms have been also faster in adapting their business strategies to the changing situation, a fact that could be associated with their overall better performance during the pandemic. Specifically, firms integrated in the international markets responded significantly stronger than domestic ones to the changing situation; indeed, they significantly started (or increase) business online activities and remote working, a stylized fact also confirmed by Webster et al. (2021). Last but not least, internationalized firms have been less prone than their domestic counterparts to reduce their temporary workforce as a reaction to Covid-19.

More research is needed, especially on the underlying mechanisms, but our work is one of the first firm-level, cross-country studies on the effect on the pandemic on international firms on a large number of countries at different level of economic development; our results contribute to the debate bringing evidence against nationalistic views, pointing to the centrality and robustness of the international production networks, as they appear to have suffered less than firms operating only in the domestic markets, probably also due to the of international firms’ higher reactiveness to shocks.

Antràs, P. (2020). De-globalisation? Global Value Chains in the post-COVID19 age. NBER Working Paper Series (No. 28115).

Antràs, P., & Chor, D. (2021). Global value chains. NBER Working Paper Series (No. 28549).

Artuc, E., Bastos, P., & Rijkers, B. (2018). Robots, Tasks and Trade. Policy Research Working Paper (No. 8674), Issue December.

Bellora, C., & Fontagnè, L. (2020). Shooting Oneself in the Foot? Trade War and Global Value Chains. (No. hal-02444899). HAL

Berthou, A., & Stumpner, S. (2022). Trade under lockdown. Banque de France Working Papers.

Bonadio, B., Huo, Z., Levchenko, A. A., & Pandalai-Nayar, N. (2020). Global supply chians in the pandemic. In NBER Working Paper Series (No. 27224).

Borino, F., Carlson, E., Rollo, V., & Solleder, O. (2021). International firms and COVID-19: Evidence from a global survey1. Covid Economics, 30.

de Lucio, J., Mínguez, R., Minondo, A., & Requena, F. (2022). Impact of Covid-19 containment measures on trade. International Review of Economics & Finance.

Espitia, A., Mattoo, A., Rocha, N., Ruta, M., & Winkler, D. (2021). Pandemic trade: COVID-19, remote work and global value chains. World Economy, 1–29.

Giglioli, S., Giovannetti, G., Marvasi, E., & Vivoli, A. (2021). The Resilience of Global Value Chains during the Covid-19 pandemic: the case of Italy. Economia Italiana.

Giovannetti, G., Mancini, M., Marvasi, E., & Vannelli, G. (2020). Il ruolo delle catene globali del valore nella pandemia: effetti sulle imprese italiane. Politica Economica.

Karalashvili, N., & Viganola, D. (2021). The Evolving Effect of COVID-19 on the Private Sector. Global Indicators Briefs No. 1.

Olczyk, M., & Kuc-Czarnecka, M. E. (2021). Determinants of COVID-19 Impact on the Private Sector: A Multi-Country Analysis Based on Survey Data. Energies, 14(14), 4155.

Rodrik, D. (2018). New Technologies, Global Value Chains, and Developing Economies. In Pathways for Prosperity Commission Background Paper Series.

Webster, A., Khorana, S., & Pastore, F. (2021). The Labour Market Impact of COVID-19: Early Evidence for a Sample of Enterprises from Southern Europe. IZA Discussion Paper Series (No. 14269)

World Bank. (2020). World Development Report 2020 - Trading for development in the age of global value chains.

[†] Department of Economics and Management, University of Florence and Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute.

[‡] Department of Economics and Management, University of Florence.