by Ignazio Musu[*]

China plays a crucial role in energy geopolitics, both in terms of fossil fuels, which still constitute the core of its energy system, and in terms of renewable energy and fight against climate change. The Belt and Road Initiative is an important infrastructure, because of oil and gas pipelines from Central Asian countries, as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and from Russia, involved in a closer relationship after the outbreak of the Ukraine war, because of the oil imports from the Middle East and because of the role of natural resources in the South China Sea, claimed by China and by other coastal countries.

Dealing with renewable resources and commitment in fighting climate change, the role of China is becoming more and more crucial: President Xi Jinping announced the goal of “have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060”. Solar, wind power, nuclear and hydrogen energy are expected to increase, so low-carbon energy are expected to reach a 75% share in 2060, contextually with a reduction of carbon (-80%), oil (-60%) and natural gas (-45%) demand.

La Cina gioca un ruolo cruciale nella geopolitica dell’energia sia nel campo dei combustibili fossili che rappresentano ancora il pilastro del sistema energetico di quel Paese, sia nel campo delle energie rinnovabili e della lotta al cambiamento climatico. Per soddisfare la domanda di energia con combustibili fossili è cruciale la Belt and Road con oleodotti e gasdotti da paesi dell’Asia Centrale come Kazakistan e Uzbeistan e dalla Russia con la quale i rapporti si sono intensificati dopo la guerra in Ucraina, con le importazioni soprattutto di petrolio dal Medio Oriente, e per il ruolo del Mar della Cina ricco di risorse fossili che la Cina contende agli altri paesi che vi si affacciano.

Nel campo delle energie rinnovabili e della lotta al cambiamento climatico, il ruolo della Cina sta diventando sempre più importante con l’annuncio del presidente Xi Jinping dell’obiettivo di arrivare al massimo delle emissioni di CO2 nel 2030 e all’annullamento delle emissioni nette entro il 2060, con la quota delle energie a basso contenuto di carbonio (solare, eolica, bioenergia, nucleare e idroelettrica) che dovrebbe salire al 75% nel 2060, quando la domanda di carbone dovrebbe essere caduta dell’80%, quella di petrolio del 60 per cento e quella di gas naturale del 45%.

Energy has been at the foundation of China’s extraordinary economic growth

China’s role in the energy geopolitics concerns both the fossil fuels field, the energy system on which the Chinese economy is still based for 85 per cent, and the renewable energy sources, required to deal with the climate change challenge. China’s importance in the energy geopolitics in the field of fossil fuels depends on the increase of imports of all the three types of fossil fuels, particularly through the most important Chinese geoeconomic and geopolitical initiative: the Belt and Road.

Belt is the set of land ways connecting China to Russia and to West through Central Asia countries, while Road is the set of sea ways connecting China to Russia through the North Sea, to the Arabian countries and the east coast of Africa through the Indian Ocean, to South-Est Asia through the South China Sea.

A crucial element of the Belt is Central Asia’s energy richness. The 2500 km oil pipeline from the eastern coast of Caspian Sea in western Kazakhstan (20 million tons/year) is crucial to oil import by China. Turkmenistan, with the gas pipeline of 3600 km (25 billion cubic meters per year) to Xinjiang in China through Uzbekistan, has become the largest gas exporter to China.

The Ukraine war has increased cooperation between China and Russia. Russia has entered in the liquefied natural gas (LNG) market to export natural gas discovered above the Artic Circle with tankers travelling the Northern Sea Route to Asia. The three thousand miles Eastern Siberian-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline (15 million tons per year) allowed Russia to eclipse Saudi Arabia as China’s number one oil supplier. China provided finance for a thirteen-hundred-mile “Power of Siberia” gas pipeline (38 billion cubic meters per year) bringing natural gas not only to China but also to other East Asian countries. In 2030 Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline (50 billion cubic meters per year) is expected to bring gas from a Russian deposit in North Sea to China through Mongolia.

On the Road, China is the biggest customer for oil flowing out of the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz. Middle East represents 47 percent of the oil imported by China e 12 per cent of its need of natural gas. Protection of oil transport through sea from Middle East has been the justification provided by China for its opening of a military base in Djibouti on the East African coast. The fact that China has to use the Indian Ocean to import fossil fuels is now the reason provided by the People Liberation Army to justify its increasing presence in the many ports opened by the Chinese on the shores of that sea. Huge investments made by China in those ports cannot be fully dependent on trade and development reasons; there also strategic reasons more generally related to the military Chinese expansion not only on the land, as it was the historical tradition, but also on the sea.

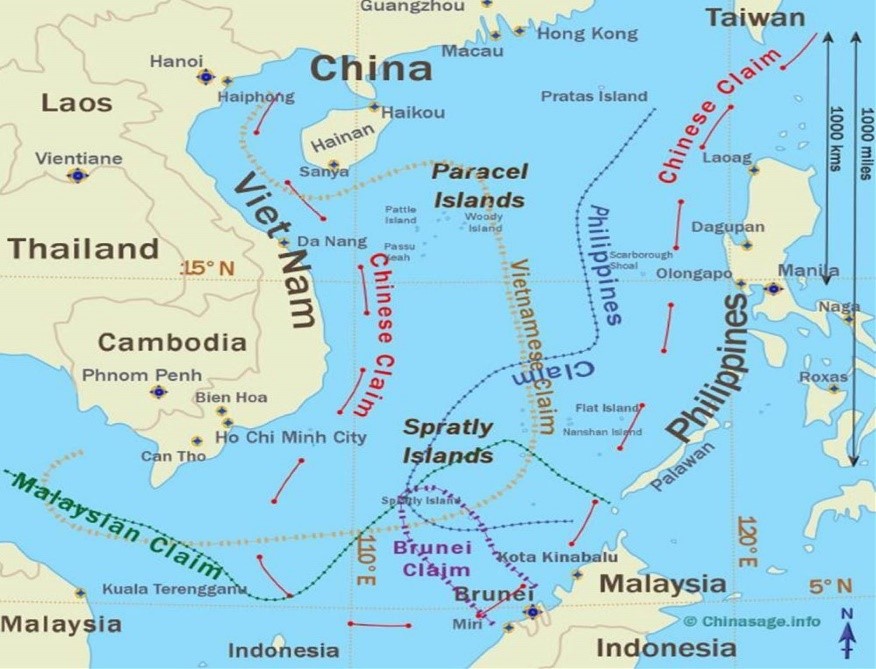

The Road passes also through South China Sea, faced by a number of countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan and China) and connected to Indian Ocean by the 1.5 miles wide Malacca Strait running between Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. South China Sea is the highway for one third of the world oil trade (15 million oil barrels per day) and one third of the world traded LNG. South China Sea is also the highway for two thirds of the sea trade of China and 80% of the oil imports by China.

Strait of Malacca

Source: Wikipedia.

Chinese refer to the “Malacca dilemma” as the risk that, in the case of war, the US navy can close the strait, inhibiting China’s access to energy and trade by sea. Adjacent to the Malacca strait, a huge project “Melaka Gateway” is being built by the Chinese in cooperation with Malaysian partners within the Belt and Road Initiative. The project, expected to be completed in 2025, includes a residential district, a financial center and a deep-water port expected to accommodate big tankers carrying oil and liquefied natural gas. South China Sea is now where the risks of a military confrontation are higher: Taiwan is located there; Diaoyu Island occupied by Japan at the end of the World War II and claimed by China are there; there is a contrast on the control of the Spratly Islands occupying a large area from Vietnam to Philippines, and of Paracelsus Islands between China and Vietnam.

The South China Sea claims

Source: South China Morning Post 2022

China claims the right on South China Sea using maps of the 17th century certifying the Chinese sovereignty; the other countries rely on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea according to which in “territorial waters”, out to 22 km from the baseline, the coastal state is free to use any resource, while in “economic exclusive zones”, extending from the baseline, the coastal nation has sole exploitation rights over all natural resources. The opposition of United States to Chinese claims on South China Sea also refer to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, although the US have not signed the Convention. Claims by the other countries didn’t succeed in blocking China from digging tons of rocks and sand to build artificial islands on which install military bases; also, their initiatives didn’t succeed in blocking China from drilling operations to oil and gas.

South China Sea has abundant energy resources, with a huge potential of oil and natural gas on the seabed; estimates are that the South China Sea holds about 60 billion cubic meters of natural gas and 10 billion barrels of oil reserves. China’s initiatives to discover and drill oil and gas resources deep beneath the South China Sea have been a source of problems with Vietnam and even with Russia. In May 2014, China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) placed a huge equipment, capable of drilling up very deeply under the seabed, in waters claimed by Vietnam east of its coasts as “territorial waters”; protests of Vietnamese in the streets led to evacuation of thousand Chinese nationals. In 2017, China threatened to attack Hanoi’s outposts in the Spratly Islands if it did not stop drilling in an area on Vietnam’s continental shelf, thus overlapping with China’s expansive claims. In July 2019, the Russian company Rosneft, in partnership with the Vietnam’s state oil company, started drilling in what Vietnam was claiming its Exclusive Economic Zone; ships from Chinese navy sent to the area sailed away only after Rosneft and its Vietnam partner stopped drilling.

The role of China in energy geopolitics also concerns its commitment in fighting global warming and climate change.

China’s yearly CO2 emissions overcame, since 2006, those of United States, making China the world most important country emitting greenhouse gases; in 2019, China’s greenhouse emissions overcame those of all the developed countries jointly considered. On the other hand, China is the biggest world producer of plants for solar and wind energy, and it is becoming the biggest world producer of batteries, crucial for storing intermittent solar and wind energy sources. China controls 90% share of the global production of downstream rare earth products, such as copper, graphite, lithium, and cobalt, used in manufacturing wind turbines, solar panels, and batteries. In extracting and processing these materials China has a first-mover advantage, as Chinese companies have invested in mines, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Chile, and Australia. In the DRC, China is estimated to have secured supply agreements with over half of the local cobalt producers; Chinese companies have stakes in projects accounting for one-third of Argentina’s lithium reserves and two-thirds of Chile’s lithium production.

Beyond resource extraction, China is also becoming dominant in battery manufacturing; CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology) in Fujan, China, has become the largest world producer of batteries with 30% of the world’s market. In 2019 China was able to sell more than half of all Electric Vehicles (EVs) sold in the world, its target being to have 40% of the vehicles sold in the country be electric by 2030; by 2025, the Chinese government aims to have in place EV charging infrastructure to meet the needs of more than 20 million cars.

In September 2020, President Xi Jinping announced that China will “aim to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060”. Also, China committed at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2021 to discontinue building coal-fired power projects abroad and to step up support for clean energy. The Chinese government asked the International Energy Agency (IEA) to write a roadmap on carbon neutrality. In the IEA Roadmap, the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), reflects China’s enhanced targets declared in 2020 in which emissions of CO2 reach a peak before 2030 and net zero by 2060. In the APS, natural gas (with a carbon footprint half of coal and a quarter less than petroleum) is the only fossil fuel growing in the energy consumption mix, to 14% from 8%; coal’s contribution has to shrink to 3% from 57%, while oil has to decline to 8% from 20%. Solar energy will rise from 1% to 22%, followed by wind power at 17% from 3%; nuclear energy’s weighting could quadruple to 8%. Hydrogen will grow from almost zero to 11%; it is currently produced mainly from breaking down coal or natural gas, and through electrolysis (using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen); but China aims at becoming a leader in producing the so-called “green hydrogen” with renewable power.

In 2021 China kicked off its national carbon-trading exchange that will become the world’s largest carbon market; when fully implemented, China’s carbon market is expected to cover more than 70% of China’s CO2 emissions by 2025, with a China’s carbon price surpassing $50 in 2030. The latest China’s Five-Year Plan accepted the IEA Roadmap, aiming to shift the focus of innovation to low-carbon technologies and pursue new policy approaches. At the beginning of November 2022, China presented the result that its CO2 emissions per unit of GDP halved since 2005, with a fall of 51% compared with 2005, and 3.8% lower than 2021, while the share of non-fossil energy consumption increased to 16.6%.

However, recent tensions between China and US, related to the Ukraine war and the question of Taiwan, may affect negatively the China’s commitment in fighting climate change.

References

D. Yergin, The New Map. Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations, Penguin Books, 2020.

P. Hogselius, Energy and Geopolitics, Earthscan, 2019.

T. Chaudhary, Climate and Energy Decoded, HopeSpring Press, 2022.

M. Stephen, The Chinese Economy, Agenda Publishing, 2021

International Energy Agency, An Energy Sector Roadmap to Carbon Neutrality in China, IEA, September 2021.

[*] Ca’ Foscari University of Venice