by Augusto Ninni - Mercatorum University, Rome

1) The Context of the Energy Transition Crisis

The crisis surrounding the energy transition did not begin with the especially negative arrival of Donald Trump as President of the United States. In Europe, the Russia–Ukraine war, which began in February 2022, highlighted for individual countries both the convenience and the necessity of reducing dependence on Russian natural gas, while forcing them to do so urgently. This urgency allowed for replacement with renewable sources—a key component of the energy transition—only in terms of upstream electricity generation. However, the process of replacing gas with electricity in final energy consumption was much more limited. According to Enerdata, in 2024 only 21% of final energy consumption was met by electricity, a share only slightly lower than in 2020.

In Europe, the energy transition has faced resistance not only from industries linked to fossil fuels but from those directly affected by the transition—such as the automotive sector—as well as from households. For this reason, the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, was compelled to temper her ambition of strengthening the industrial competitiveness of the EU-27 by aligning it with the energy transition. This adjustment was evident in her two State of the Union addresses, marking a shift from the Green Industrial Deal of December 2019 to the Clean Industrial Deal of December 2024.

Notice that in Western countries, renewable energy production has also been curiously hindered by local opposition to the installation of new solar and, in particular, wind power facilities. The reasons for opposition vary, but the defense of the landscape is the most frequently cited justification.

2) The Trump Administration and Its Impact

The return of Donald Trump to the presidency has further exacerbated the situation. Upon taking office on January 20, 2025, he:

Immediately withdrew the United States from the 2015 Paris Agreement;

- Extensively promoted electricity generation from fossil fuels;

- Terminated U.S. participation in several international public financing initiatives supporting the energy transition in emerging countries;

- Repealed the Inflation Reduction Act—previously the most comprehensive public financing initiative for the energy transition in Western nations—replacing it with the Big Beautiful Bill;

- Declared open hostility toward wind energy, most notably by blocking the nearly completed Revolution Wind offshore project, thereby causing serious financial difficulties for Ørsted, a leading Danish renewable energy firm;

- Signed an agreement with Ursula von der Leyen under which the European Union committed to importing $750 billion worth of energy (primarily LNG) from the United States by 2028—a plan widely regarded as unfeasible on both the European demand and U.S. supply sides, and inherently contradictory to the aims of the energy transition.

Moreover, shortly after Trump’s election victory—but before he officially took office—six major U.S. banks (JP Morgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo, and Goldman Sachs) withdrew from the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), an initiative aimed at channeling private savings into renewable energy projects in developing countries.

Given the repositioning in energy supply in the United States—and more broadly in Western countries—toward directions inconsistent with the goals of the energy transition, an essential question arises: can the transition, conceived as a “global common good,” still be achieved through the actions of emerging economies, even if over a longer time horizon than previously considered acceptable?

3) The Role of Emerging Economies

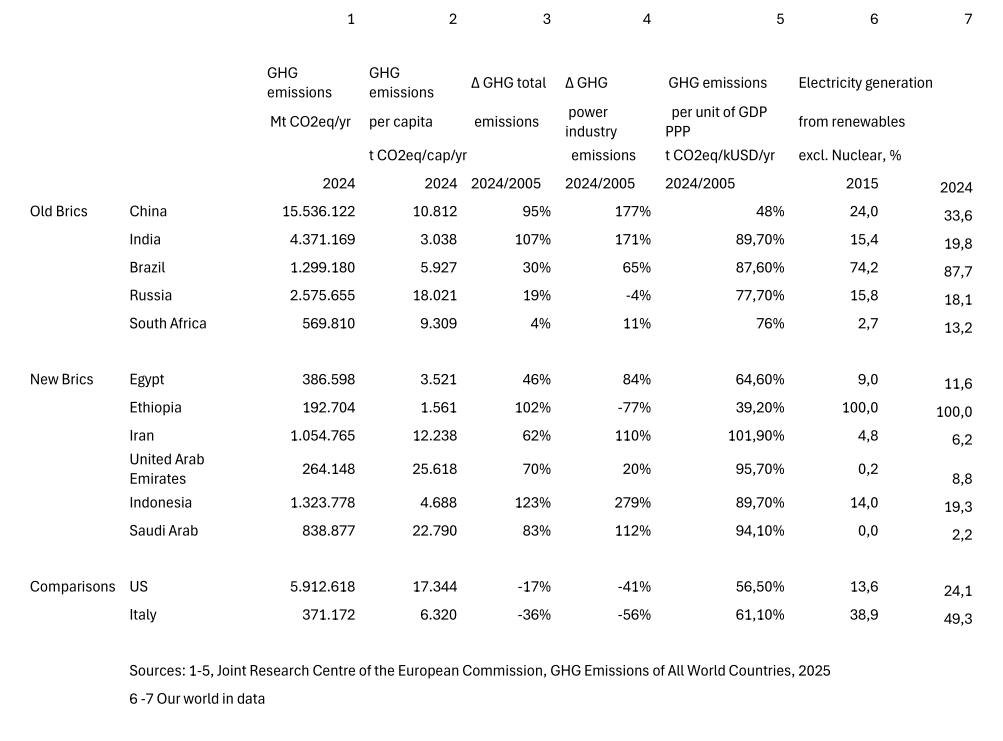

To address this question, it is useful to focus on the BRICS group, now expanded to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia. Together, these countries accounted for 53% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2023. For comparison, data for the United States and Italy are also included in Table 1.

In the cases of China—and to a lesser extent India—a persistent contradiction exists. On one hand, these countries are among the world’s largest emitters (China alone accounts for 26% of global GHG and 34% of CO₂ emissions, excluding LULUCF). On the other hand, they are leaders in renewable energy manufacturing, with approximately 80% of global solar and 60% of wind production capacity. Their growth in renewable deployment has also been particularly strong.

Between 2005 and 2024, all BRICS countries increased their emissions (col. 3), whereas the United States and Italy reduced theirs. China and India nearly doubled their emissions, as did Ethiopia and especially Indonesia. However, these increases were largely attributable to economic growth (col. 5): in most cases, emissions rose less rapidly than GDP in purchasing-power-parity terms, except in oil-exporting countries. In China’s case, the growth in emissions amounted to approximately half the rate of GDP growth.

A substantial share of these emissions originated from electricity generation (col. 4). In China, India, and Indonesia, economic growth was driven primarily by fossil fuels, which significantly increased emissions—unlike in the United States or Italy. However, a comparison of 2015 and 2024 (cols. 6 and 7) reveals that the share of renewables in electricity generation increased across all countries, including oil exporters (except Ethiopia, where more than 90% of generation already derives from hydropower).

4) Industrial Policy and the Energy Transition

In recent years, all BRICS countries—albeit to differing extents—have undertaken measures toward an energy transition, with increases in renewable shares comparable to those observed in Western countries. The key questions are whether these efforts can continue amid the current crisis in the global energy transition, and what role industrial policy plays in this process. For reasons of space, the discussion focuses on the five largest emitters, which also have the most extensive industrial capacities.

China began investing in renewable energy primarily as an instrument of industrial policy, seeking to create a domestic supply base capable of meeting growing global demand for “green energy,” particularly in Europe, where consumption incentives were strong (Ninni, Lv, Spigarelli, & Li, 2020). Continuous expansion has granted China a dominant position in the manufacturing component of renewable power plant costs—accounting for about 50% of total utility-scale photovoltaic costs. This leadership has driven significant cost reductions, making renewable-based electricity generation considerably cheaper than that from fossil fuels worldwide.

However, as in other Chinese industries, persistent overcapacity has emerged, sustained by substantial government subsidies and the availability of low-interest provincial loans. Recently, President Xi Jinping announced a plan to reduce China’s CO₂ and other GHG emissions by 7–10% by 2035 and to increase the share of electricity generated from renewables by 30% over the next decade.

India’s development path mirrors China’s on a smaller scale. A rapid expansion of renewable energy production—with the goal of becoming a major net exporter before 2030—enabled India to reach its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) target of 50% renewable electricity capacity five years ahead of schedule. However, the pursuit of high economic growth without explicit emissions-reduction targets—many of which depend on conditional foreign loans—and heavy reliance on fossil fuel imports cast doubt on its ability to sustain progress, particularly in light of Trump’s withdrawal from climate finance initiatives and his rapprochement with Russia to expand gas exports.

Russia’s case is more straightforward. In September 2025, President Putin presented to the UNFCCC a plan pledging to reduce emissions by 33–35% by 2035 relative to 1990. Yet, according to the Climate Action Tracker, this pathway corresponds to a “business-as-usual” scenario, contrary to the Paris Agreement’s requirement for extraordinary efforts in Nationally Determined Contributions. The Energy Strategy for 2050 (2025) confirms that coal will continue to represent a share of the energy mix ten times greater than that of wind and solar, underscoring Russia’s enduring reliance on fossil fuels.

Among the countries analyzed, Brazil stands out for its abundance of clean energy resources—primarily hydropower—which places it furthest along the energy transition pathway. However, its emissions have stagnated, and the country has failed to meet its 2025 target, with the 2030 goal also appearing unattainable. Long-term plans project a growing role for gas and oil production over the next decade, despite Brazil’s formal commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

Indonesia exemplifies the broader challenges faced by emerging economies. Despite its stated ambition to increase reliance on renewable energy, the country’s economic growth remains heavily dependent on domestic coal. Rising emissions are also driven by deforestation linked to palm oil production. (By contrast, in Brazil, President Lula has tightened deforestation controls compared with the Bolsonaro administration.) Indonesia’s draft 2035 NDC remains modest, with a net-zero target postponed to 2060 and outcomes heavily dependent on foreign investment—its “conditional” pledges are far larger than its unconditional ones.

5) Conclusions

The findings of this brief analysis are sobering. Among the major emerging economies—five of which together account for approximately 47% of global GHG emissions—only China appears both capable of and committed to sustaining its energy transition. This is largely due to its industrial capacity to manufacture renewable energy systems and to control the entire value chain: upstream (rare earths and critical raw materials), midstream (batteries), and downstream (electric vehicles). The only uncertain variable that may affect this trajectory is the prospective expansion of gas imports from Russia via pipeline, proposed in Beijing in early September 2025.

Excluding Russia, which shows little inclination toward decarbonization, the remaining countries are significantly constrained by the sharp contraction in international climate finance—largely resulting from Trump’s policies. India, although developing its own renewable industry, remains far behind China, constrained by raw material shortages and its reluctance to rely on its geopolitical rival. Brazil and, to a lesser extent, Indonesia remain relatively weak in the solar and wind sectors, having failed to establish coherent industrial strategies in these fields.

It is therefore likely that China represents the exception: the crisis of the global energy transition is real and ongoing—not only among emerging economies but within the entire international community.

References

Climate Action Tracker. (2025). Country assessments: Russia. https://climateactiontracker.org

Daniele, F., de Blasio, G., & Pasquini, A. (2024). Is local opposition taking the wind out of the energy transition?, GSSI Discussion Paper Series, (2024-13), 1–25.

Enerdata. (2024). Global energy consumption statistics. https://www.enerdata.net

European Commission. (2024). State of the Union addresses (2019–2024). Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union.

Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. (2025). GHG emissions of all world countries 2025. European Commission.

Ninni, A., Lv, P., Spigarelli, F., & Li, P. (2020). How home and host country industrial policies affect investment location choice? The case of Chinese investments in the EU solar and wind industries. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics / Economia e Politica Industriale, 47(1), 55–82.

Radtke, J., & Low-Beer, D. (2025). Unpacking local energy conflicts: Drivers, narratives and dynamics of right-wing populism and local resistance to energy transitions in Germany. Energy Strategy Reviews, 61, 101844.

Sanchez Nieminen, G., & Laitinen, E. (2025). Understanding local opposition to renewable energy projects in the Nordic countries: A systematic literature review. Energy Research & Social Science, 122, 103995.