By Vittorio Valli, University of Turin; Fondazione L. Einaudi -Torino and OEET[1]

Questo scritto è una rielaborazione in lingua inglese, arricchita ed aggiornata al 22 maggio 2020, della nota del 13 Aprile 2020, che era stata pubblicata in lingua italiana su questo sito. La tesi principale è che l’Italia e, in successione, diversi altri paesi occidentali come il Belgio, la Spagna, il Regno Unito, la Francia, la Svezia e gli Stati Uniti, non hanno imparato, né dalla Cina, né dalle grandi democrazie dell’Est Asia, come il Giappone e la Corea del sud, a reagire con adeguata prontezza ed efficacia alla devastante avanzata della pandemia. Essi hanno quindi pagato un prezzo assai più alto dell’Est Asia in termini di decessi e di crisi economica e sociale. Questo dipende soprattutto da quattro fattori. Il primo è il vasto e ingenuo uso di dati fuorvianti ed inaffidabili come i “casi positivi ai test” come indicatore principale del livello e degli andamenti dei “contagi”, che invece sono un numero sconosciuto e grandemente più elevato. Il numero di casi positivi dipende infatti dal numero di test fatti, dalle priorità con cui sono stati fatti, dalla fase della pandemia e dalle politiche di contenimento messe in atto in ogni periodo dai governi. Inoltre questo indicatore non tiene conto il più delle volte dei contagiati asintomatici che contribuiscono fortemente alla diffusione della pandemia. Un dato assai meno incerto, sebbene anch’ esso variamente sottostimato, è quello dei decessi attribuibili al Covid-19. Secondo questi dati, il confronto, ad esempio, tra la Corea del sud e l’Italia, ma anche altri paesi occidentali, è impietoso. Fino al 22 maggio 2020 la Corea del Sud aveva avuto 5 morti per ogni milione di abitanti, l’Italia 539, la Spagna 612, il Regno Unito 536, la Francia 433, gli Stati Uniti 295 ed il Belgio addirittura 795. Perfino paesi più accorti, come Germania e Grecia, avevano avuto rispettivamente 100 e 16 morti per milione di abitanti. Gli altri fattori principali sono il ritardo della conoscenza, la presunzione dell’Occidente e le ragioni economiche e sociali che hanno influenzato i governi nazionali e regionali. Quest’ ultimi non hanno avuto il coraggio politico di reagire prontamente e con adeguata efficacia all’attacco della pandemia. Le analisi comparate tra le politiche dell’Italia e della Corea del Sud e, all’interno del Nord Italia, tra la Lombardia ed il Veneto, oltre all’esame dell’importante caso della cittadina veneta di Vo’, consentono di comprendere meglio il grande contrasto tra le politiche adottate nella Corea del sud e in Italia ed i loro esiti e quello tra il disastro lombardo e la pesante, ma più contenuta, esperienza del Veneto.

Prologue

It might be presumption, racism or simply ignorance, but it is a fact that the political leaders of most Western countries have not learnt from the experience of Eastern Asian countries after the outbreak of the great coronavirus crisis. They have poorly studied and badly utilized the experience of China and of other Eastern Asian countries which have preceded them in the fight against the great pandemic.

South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have profitably studied the experience of Wuhan, Hubei and the other Chinese zones badly hit by Covid-19. They have so reacted to the epidemic much more promptly, and with greater vigor and completeness than most European and North American countries and therefore, in proportion to their population, they have had less suffering, less deaths, and less devastating social and economic crises.

South Korea versus Italy

Let’s take, for example, the case of South Korea versus the case of Italy. Both South Korea and Italy discovered the first cases of imported Covid-19 in the second half of January 2020 (20th January South Korea, 29thJanuary Italy), but most probably in both countries the contagion was already present also in the first half of January due to the great number of business and personal contacts with China of the two countries.

South Korea reacted more rapidly and with more strength than Italy,[2] especially when, since February 19th in the city of Daegu (2.5 million people) a great meeting of the religious group Shincheonji had massively contributed to the diffusion of the virus. There were, in rapid sequence, the partial closure of the Daegu area; restrictive measures in the whole country, but no complete lockdowns; a great number of tests, and the relentless and well-organized tracing of people who had been in close contact with the infected people. These people too, even if asymptomatic, were massively tested. A special app applied to the mobile phones helped the research. If found positive to the tests, infected people were quarantined in a great number of assisted structures or at home and, in the more serious cases, sent to hospitals. Twice a day a phone control had been organized for people isolated at home. It has so been possible to avoid, with the exception of the first weeks in Daegu, the collapse of the overwhelmed hospital system, as it had happened initially in China at Wuhan, in Italy at Codogno, Piacenza, Bergamo, Brescia and Milan, in Spain in Madrid and other cities, and as it is happening in Belgium, France, United Kingdom and in New York and other US cities.

Before the outbreak of the Coronavirus crisis, South Korea had also the great advantage of having, like Japan and Germany, a much higher number of hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants than France, Belgium, Italy, Spain, United States, United Kingdom and Sweden. It had also promptly programmed the expansion of Intensive care units (ICU) and the internal production or purchase of a great number of swabs and reagents, ventilators and masks, while, for example, Italy, Spain, Belgium, the UK, have moved with great delay, when a large part of these goods had already been bought up by other countries and it was difficult to internally produce them in restricted times. In South Korea the presence of adequate personal protective devices has powerfully contributed to prevent hospitals, old people’s homes and doctors’ offices from becoming dangerous contamination places both for medical personnel and their patients, and to limit the diffusion of the contagion within the population. On the contrary, in Italy and in Spain individual protective units were scarce and difficult to obtain. In two-three weeks in South Korea the prompt large use of tests, of tracing practices and of social distancing heavily contributed to block the critical phase of exponential growth of the contagion, though productive activities were only in part closed. The large number of beds and of ventilators widely reduced the mortality in hospitals. By all these means, in South Korea, the contagion had been soon contained and in only three weeks, by March 10, it had been circumscribed, though not spent. The result of all this has been: from mid- February 2020 to 16th May, 262 total coronavirus deaths in South Korea, versus 34,466 in the UK, 27,563 in Spain and 31,763 in Italy; that is, for every million inhabitants, about 5 in South Korea, 508 in the UK, 590 in Spain and 525 in Italy, 105 times the East-Asian country. Moreover, even at present, in the UK, Italy and Spain, the number of deaths, though declining, continues to be very high, while in South Korea the number of daily Covid-19 deaths has constantly been inferior to 10 people. On 16th May, there were two new deaths in South Korea versus 468 in the UK, 104 in Spain and 153 in Italy. A part of these deep differences between South Korea and Italy can be explained by the larger share of elder people in Italy or their gender distribution, since elder persons are more vulnerable than younger ones and elder women seem to be less affected by the virus than elder men. Yet, the largest part of the difference is due to policies, not to aging or gender. Long -run policies have shaped the pre-existing health system, and the latest tree-month policies have heavily influenced the overall results in terms of sufferings, deaths and social-economic disruption.

A weak and misleading indicator

One important determinant of the tardive and erroneous policies carried out in most Western countries has been the very wide use, by the WHO, and by most European and American experts, politicians and mass-media, of an incomplete and misleading statistical indicator: the total number of cases resulting positive to the tests, confirmed by the National health authorities. Many people have confused this indicator with the true number of infected people, which is instead totally unknown, as it had not been possible to extend the test to the entire population. According to rather rough estimates of several experts, the second indicator (the true number of infected people) might be at least between 5 and 10 times higher than the number indicated by the first indicator, every day presented with great resonance to the public by the health authorities. A study of the Imperial College, issued on March 30, 2020,[3] even sustains that, on 28th March, Italy had 5.9 million infected people, over 45 times the people found positive to the tests on that date.

The problem associated to a very bad indicator as the total number of confirmed cases resulting positive to the tests, is that the indicator crucially depends on three factors: a) the number of tests carried out, b) the priority criteria used by the health authorities in running the tests, and c) the stage of diffusion of the contagion. If in two countries there is the same number of truly infected people, but in country A many tests are run while in country B few tests are run, of course the indicator will give a much higher number for the first country. If two countries carry on the same number of tests, but in country A the health authorities decide to run the tests only to people with clear symptoms of Covid-19 and in country B they decide to test also a part of the population which appears asymptomatic, or feebly symptomatic, of course country A will appear to have a higher number of positive cases than country B, but it also will have a great number of undetected infected people freely spreading the contagion within the population. Finally, if numerous tests are applied in the very first days of the diffusion of the contagion, they can give an already underestimated, but relatively close value of the true number of infected people; however, only a few days later, given the exponential growth of the contagion, the same number of tests will give a hugely underestimated number, and the gap between the indicator and the true number of infected people will very rapidly grow in absence of severe restrictive measures or an exponential growth in the number of tests. Therefore, the validity of the indicator varies over time and depends also on the effectiveness of the policies of containment and of testing operated by the authorities. In conclusion: not only is the indicator in question a rough and misleading tool, but also the widely diffused comparisons over time for any given country and the ones among countries based on this indicator are misleading and have to be taken with very great caution.

The comparison between South Korea and Italy, shows also that from mid-February 2020 to mid-March the former began the tests sooner, made a much larger number of tests than Italy [4] and a part of them were targeted to the people operating in hospitals and old people’s homes, and, thanks to extensive tracing, also to the people in contact with persons resulting positive to the tests. It was therefore possible to soon detect and isolate a large number of asymptomatic, but infected, people and prevent them from rapidly spreading the epidemic. On the contrary in Italy, for the combined effect of the lack of materials and labs for tests, the WHO’s initial erroneous indications to operate the tests only to symptomatic people and the great delays in using adequate restrictive measures, the contagion could expand much more rapidly and in great part in a treacherous, silent and undetected way. A bit later than in Italy, the same happened in France, the United Kingdom, the United States and, even with more deadly results than in Italy per each million inhabitants, in Belgium and in Spain.

Testing very soon in an extensive way, in order to detect also asymptomatic infected people and readily contain the contagion, was indeed decisive, as the South Korean case clearly indicated.

A survey with a great number of tests applied to a large sample of the country’s population would have been very important in order to evaluate the diffusion of the pandemic and better design the national and regional containment policies.[5]

The case of Vo’

In Italy there was a culpable delay in the perception of the need to soon detect and isolate also the asymptomatic cases, although since the first half of March we might have profited from the preliminary results of an important study about Vo’. [6] Vo’ is a small town of 3,275 people, close to Padua in Veneto, where on February 21, 2020 there was the first death in Italy due to Covid-19. The national and regional authorities imposed the lockdown of the whole town for 14 days and a research team of the University of Padua, directed by professor Andrea Crisanti, could examine and test about 86% of the entire population. Two surveys, based on pharyngeal swabs, were conducted at the beginning and at the closing of the lockdown. The first survey regarded 2,812 people, the second one 2,343 subjects, respectively 85.9% and 71.5% of the total eligible population of the small town.

The main results of the tests were:

- in the first survey 2.6% of the tested subjects resulted infected (73 people); in the second survey 1.2% (29 people), of which 8 were new cases.

- in the first survey the 41.1 % of the positive cases (30 out of 73) was completely asymptomatic; in the second survey 44.8% (13 out of 29).

- the age distribution of all positive cases showed no symptomatic and asymptomatic cases for children of 0-9 years of age; relatively few symptomatic and asymptomatic cases for each ten-years age groups up to 50 years; a larger amount of both symptomatic and asymptomatic positive cases for over 50 years age groups, and in particular for the 71-80 age group; only 4 positive symptomatic cases and one asymptomatic for people of 81+ years. It must be noted that for the age group of 31-40 years, usually a very mobile and dynamic group, and so likely to have multiple contacts, there were more asymptomatic people (6) than symptomatic ones (3) in the two surveys.

- most of the 8 new infection cases were due to infections taken before the lockdown or from asymptomatic people living in the same household.

- the viral loads of symptomatic and asymptomatic people were very similar.

The study of Vo’ could indicate that a policy centered on early lockdowns; more tests, directed also to asymptomatic people; more tracing and isolation measures and more protection for health operators and old people, could effectively contain the rapid diffusion of the epidemics, as it had occurred in South Korea and in other East Asian countries. In Vo’, after about one month from the beginning of the lockdown, Covid-19 was totally eradicated. However, in Italy, only in Veneto the indications of Andrea Crisanti and his collaborators were partly followed. In that region, a more timely, extensive and targeted use of tests with respect to Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, Piedmont and Liguria, contributed to considerably reduce the death toll, slowing down the escalation of the epidemy and preventing Veneto’s hospitals and retirement homes from being brutally overwhelmed. Up to May 16th 2020, Veneto had 363 Coronavirus total deaths per million inhabitants, versus 819 in Piedmont, 857 in Liguria, 890 in Emilia Romagna, 1542 in Lombardy. However, Veneto was very distant from the South Korean result (5 deaths per million inhabitants) mainly because of the much delayed and less efficient response in terms of individual protective devices, lockdowns and tracing.

About coronavirus mortality

Since we ignore the true number of infected people in any country or region, the use of the fatality rate, defined by the number of coronavirus deaths divided by the confirmed positive cases resulting from the tests, has a very low scientific value. As we know, the denominator of the rate strongly undervalues the true number of infected people. Moreover, also the numerator is problematic. Usually, deaths lag about two weeks after the time of the first positive test; the data on coronavirus deaths of several countries underestimate the true number of deaths directly or indirectly due to the virus, since they often take into account only the deaths occurred in hospitals, not the ones occurred at home, or in the old people’s homes. In order to roughly measure the effects of the coronavirus on mortality it would be better to look at the number of deaths occurred in the period of the pandemic compared with the average of the deaths occurred in the same period in the previous 5 years corrected for population changes. For Lombardy, and in particular for the provinces of Bergamo, Brescia and Milan these estimates are appalling and much higher than the official figures on coronavirus deaths. The estimates for Italy, but also for other countries and cities, such as the United Kingdom, Spain, France and New York, are also considerably higher than the official figures.[7] Notwithstanding the fact that the official data of coronavirus deaths are largely underestimated and not fully comparable between countries, these data are much better, or not so poor, as the figures of confirmed positive cases. Table 1 can so give a rough idea, even taking into account the disparities in the age distribution of the population,[8] of the enormous differences between the effectiveness of policies operated in almost all the major Western European and North American countries[9] and the major Eastern Asian countries: China, Japan and South Korea.

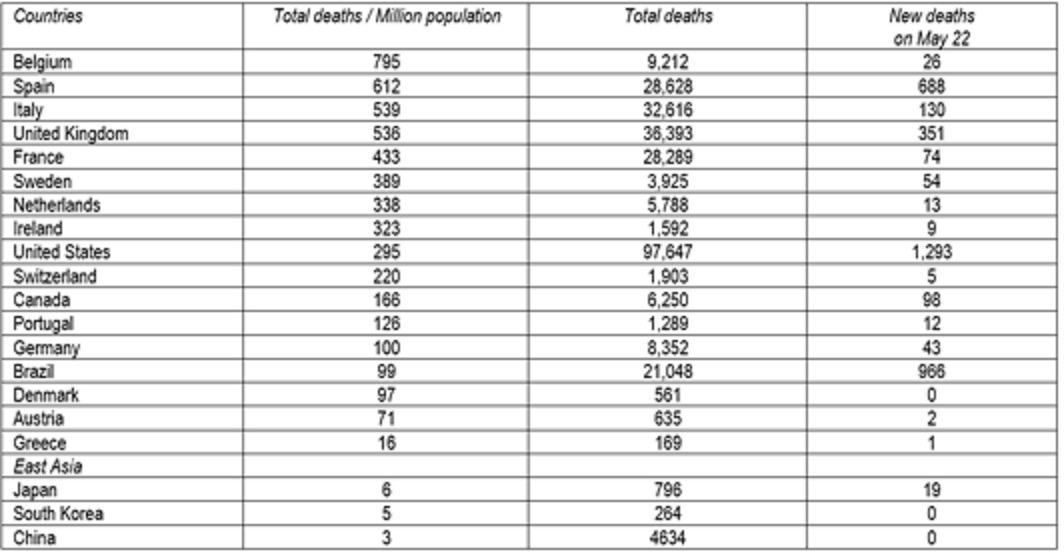

Table 1 Official cumulative coronavirus deaths up to 22nd May 2020 in selected countries

Source: The data are extracted from < https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ >, retrieved on May 23, 2020.

As we can see in Table 1, if we consider the total official data on coronavirus deaths per million inhabitants up to May 22, the worst results are those of Belgium (795 deaths per million people), followed by Spain (612), Italy (539), the United Kingdom (536) and France (433), but the UK, the United States and Brazil are rapidly worsening their position. On the contrary China, Japan and South Korea were containing their rate under 6 deaths per million inhabitants. In terms of absolute values, the US had 97,647 deaths, more than the US deaths in the Korean or the Vietnam wars, and the Covid-19 death toll continues to grow.

Why have we not followed the East- Asian examples?

Why the examples of South Korea and other East Asian countries and the teachings from cases such as Wuhan, Daegu and Vo’, have not been followed by Italy and by other Western countries such as Spain, France, Belgium, United Kingdom, Sweden, Switzerland, the United States, all countries with good medical scientists and modern, though often unbalanced, health systems? First of all, there are two very important factors: the delay in knowledge and the socio-political lag.

The delay in knowledge, suffered by most medicine doctors, virologists and epidemiologists and, even more, by the politicians and social scientists of Western countries, is partly due to the novelty of the virus and to the fact that the information coming from China on the coronavirus has been tardive and reticent, but also to the fact that all information coming from other East Asian countries, such as South Korea and Japan, have been ignored or strongly undervalued. In Europe and Canada there has been an evident cultural subjection to the great Anglo-American research. Yet, the massive diffusion of the pandemic had arrived later in the United States and the United Kingdom than in East Asia and in Italy, so that the US and British researchers and experts had initially much less direct experience about the new virus than the researchers and health services of China and nearby countries, such as South Korea and Japan.

The socio-political lag has also powerfully contributed to delay an effective response to the virus. A lag of two-three weeks in the initial phase of exponential growth of the pandemic is a tragical error. It can cost millions of infected people, several thousand deaths and a much wider economic and social crisis. The big corporations, the business associations and million entrepreneurs and operators of industry and constructions and of trade, tourism, transportation, culture, sports, banking and other services, exercised an enormous pressure on political leaders, mass-media and the public opinion in order to avoid the high economic damages due to early severe restrictive measures and the lockdown of entire cities, regions or countries. They had not understood that “a stitch in time saves nine”, that a prompt and vigorous response would have avoided the exponential growth of the contagion and the much higher and prolonged economic and social crisis destined to start only a few weeks later. Moreover, at first, a large part of the population was badly influenced by the use of erroneous indicators, by a few misguided experts who spoke of Covid-19 as “ a little more than a simple influenza”, by the weak and reticent attitude of the WHO, and finally, by the fact that some mass-media and several political leaders, such as Matteo Salvini, Attilio Fontana, Alberto Cirio, Nicola Zingaretti and Giuseppe Sala in Italy, Emmanuel Macron in France, Boris Johnson in the UK and Donald Trump in the United States, initially grossly underestimated the dangers associated to the pandemics. So, in late February and at the beginning of March 2020, a large part of the population was reluctant to accept measures which would restrict movements and social relations and introduce social distancing and closure of schools, universities, economic activities, entire cities or regions and, pro tempore, even a reduction in privacy. The governments, and the regional and local authorities of most Western countries had not the political courage to intervene as promptly and vigorously as the great East-Asian democracies: Japan and South Korea, which, with China and other countries, had previously had to face serious, but less widespread, epidemic, such as SARS and MERS.

In mid- February 2020, in some Western countries, the internal presence of Covid-19 was already known. Yet, the response was non-existent or very weak. In several political leaders It seemed to reign the crypto-racist and nationalistic idea that “this Chinese virus cannot touch us: we the Italians, we the Spanish, and, of course, we the French, we the Germans, we the British, we the Americans, can easily defeat it if it comes…”.

For example, in the second half of February, in Europe the governments, as well as the regional and local authorities and the sport federations, permitted several National League, Champions League and Europe League soccer matches, with giant stadiums open to the public, therefore activating domestic and international movements and contacts between several thousand people for each event. Moreover, even on March 10 and 11, when the pandemics was rapidly escalating, they authorized other Champions League matches without public, but permitted the assembling of large groups of fans just outside the stadiums. In some European countries and in the United States, several fairs, concerts and other public events continued up to mid-March, powerfully contributing to spread the pandemic.

More on the Italian case

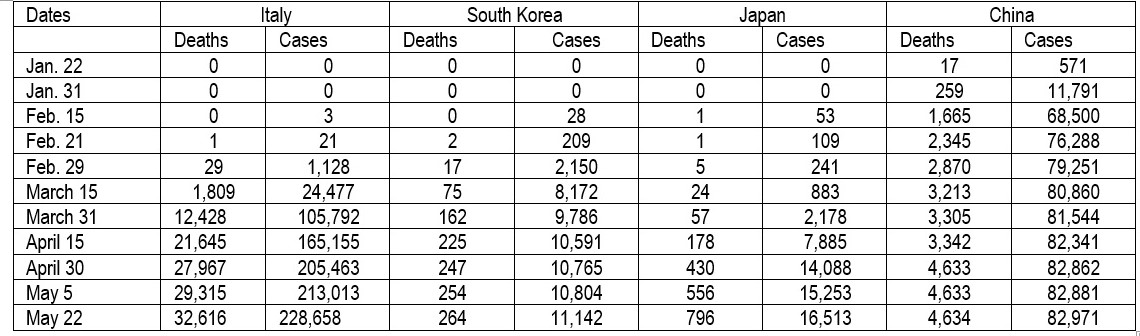

Italy was the first European country badly hit by the pandemic. After the first positive case of two Chinese tourists at the end of January, of an Italian citizen on February 20 in a small town in Lombardy (Codogno) and the first coronavirus death in Vo’ on February 21, the growth of deaths and positive cases was very rapid. In only 8 days, from February 21 to February 29, the coronavirus deaths increased in Italy from 1 to 29, soon surpassing the number of deaths in South Korea (17) and in Japan (5) (see Table 2).

In those few days the number of positive confirmed cases went up in Italy from 21 to 1,128, versus 2,150 in South Korea and 241 in Japan, which had imposed much more severe controls at airports and ports, but had made less tests (in those days tests were very abundant in South Korea, limited in Italy and relatively low in Japan).

In March 2020 the escalation of the pandemic in Italy, and in particular in Lombardy, in several zones of Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, Liguria and Piedmont and in the province of Pesaro-Urbino, was devastating. The number of deaths skyrocketed and on March 19 it surpassed the one of China, which had a population about 24 times higher than Italy. From March 19 to April 9, Italy was the country with more coronavirus deaths in the world, although, since mid-March, Belgium had more deaths per million inhabitants than Italy. Thereafter, the United States surpassed and largely distanced Italy, becoming by far the country with more coronavirus deaths, and at the beginning of May also the United Kingdom overtook Italy in this gloomy ranking.

Table 2. Total cumulative coronavirus deaths and cases in Italy, South Korea, Japan and China (a)

(a) Total cumulative deaths and total cumulative confirmed positive cases. The data were extracted on May 23, 2020 from < https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ >

In Italy the very rapid rise of cumulative deaths and cases continued also in April and the beginning of May, although the daily rate slowly decelerated after the third week of March. At regional level Lombardy (about 10 million inhabitants) was the Italian region more badly hit by the pandemic.[10] On 17th May 2020, the number of total cumulative Covid-19 deaths in the region was 15,519, almost half of the Italian death toll and over three times the total Covid-19 deaths of China. Moreover, the official Covid-19 data for Lombardy, as well as for several other regions and countries, are significantly underestimated, being mainly based on hospital Covid-19 deaths, while many deaths had occurred also at home or in old people’s homes.

A recent ISTAT-ISS study[11] presents the comparison between the deaths registered in Italy from 20th February to the end of March 2020 and the annual average of the deaths registered in the same period in the preceding five years. The report shows that the number of excess deaths (total deaths minus the average 2015-2019 deaths) was very high (in Italy about 85% higher than the official Covid-19 deaths) and strongly dissimilar between regions (see Table 3). In Northern regions, and in particular in Lombardy, the amount of total deaths was extremely high and much larger than the average of the same period in the five preceding years. Moreover, In Northern Italy, excess deaths were about 90% higher than the official Covid-19 deaths, which thus resulted strongly underestimated. On the contrary, in the Center-South total deaths were much closer to the average of the data of the same period in the five preceding years and Covid-19 deaths were relatively limited. In four Center-Southern Regions (Lazio, Campania, Basilicata and Sicily) excess deaths were even negative and inferior to the Covid-19 official deaths. In Northern Italy some provinces have suffered much more than other provinces from the direct and indirect effects of the Covid-19 pandemics. For example, from 20th February to March 31, the excess deaths were 5058 in the province of Bergamo, 3065 in that of Brescia, 2502 in the much more populous province of Milan, 1503 in that of Cremona, 950 in the province of Parma, 834 in that of Piacenza, 792 in the province of Lodi, 666 in the province of Turin, and so on. Taking account of its population, inferior to the ones of Milan, Turin and Brescia, the province of Bergamo[12] was also the most devastated by the deadly consequences of the virus, as the shocking video about a long line of grey army trucks transporting the coffins out of Bergamo has cruelly shown.

The impact of the pandemic was in Italy aggravated by delayed and partly erroneous policies. The government had blocked the direct flights from China since January 30, but had not adequately screened the indirect flights to Italy via other European countries. So, many Chinese or Italian people, or foreigners who had contacts with persons coming from Chinese infected areas, arrived at Italian airports without any control, or after the simple control of the temperature. But a large part of asymptomatic, or feebly symptomatic, infected people have no fever and they could freely enter the country and spread the pandemic, as it happened with a German man coming from Munich after contacts with Wuhan people and who contributed to the creation of a large Covid -19 cluster in Lombardy. On January 31, 2020 the Italian government declared the state of health emergency, but the government, the civil protection and the regions (which are largely responsible for the regional health systems) at first did very little for the planning and implementation of a safe and abundant external supply, or internal production, of tests, masks and ventilators and for a rapid increase of hospital beds and “intensive cure units” (ICU). Moreover, the Italian health and civil protection authorities did not succeed in organizing an efficient way to do an adequate and timely number of tests within and outside the hospitals; to create a reliable network for tracing the people who had had contacts with infected people; to establish an adequate number of assisted structures for the isolation of people suspected of being infected. On February 23, 2020 the government and the regional and local authorities decided to declare “red zones” and to impose a severe lockdown in two Covid-19 clusters: Vo’ in Veneto and Codogno and other nine municipalities in the province of Lodi in Lombardy. While the experience of Vo’ was quite successful, the one of Codogno and the other nine municipalities, with an overall population of almost 54,000 people, was very difficult. It was not possible to test all the population like in Vo’ and so a number of asymptomatic infected people continued to spread the contagion within the families and the hospitals. The hospitals of Codogno, Cremona, Crema, Mantova, Piacenza and Parma were overwhelmed and had not enough beds and ICUs, notwithstanding the help of some hospitals of Pavia and Milan. Therefore, in the three-four weeks after the lockdown, the number of deaths and positive cases continued to be very high, and slowly declined since the end of March.

Table 3. Istat-ISS data on deaths in Italy in the period 20th February- 31st March 2020

(a) column (1) – col. (2); (b) Excess deaths – Covid-19 deaths; (c) col. (5)/ col. (4) in %.

Data extracted from ISTAT- ISS, (May 4, 2020), p. 8. Retrieved on May 7, 2020. Our elaborations. < https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/05/Rapporto_Istat_ISS.pdf >.

In Lombardy, despite the exponential growth of the contagion since the end of February and the request of many local administrators in favor of a more general and severe lockdown of the whole region, the regional and national authorities had not the courage of declaring “red zones” the provinces of Bergamo and Brescia, or the entire region including the city of Milan, also because of the resistance of powerful economic and financial interest groups in the richest and most highly industrialized Italian region. In March also the hospitals of Bergamo, Brescia and Milan became overwhelmed notwithstanding the hasty attempt to add new structures. Many hospitals and old people’s homes, besides being stoic centers of care, became also centers of diffusion of the virus.

The national government adopted weak and scarcely incisive restrictive measures on February 25 and March 1, 4, and 8, deciding also the closure of kindergartens, schools and Universities, which partially continued their activities on-line. Yet, only on March 9 (decree “I stay at home”), March 11 (closure of non- essential commercial activities), and finally on March 22 (blocking of movements towards other municipalities, but for a few motivated exceptions, and further restrictions in economic activities), did the government impose “social distancing” in the whole country and the drastic reduction of movements out of home, except for essential working activities and the purchase of food and medicines. These measures contributed to contain the diffusion of the pandemic, but the number of Covid-19 deaths remained very high, beginning gradually to decrease, on a daily basis, only from the beginning of April. Finally, on May 4, there was the beginning of a new period (phase 2), in which the government permitted the opening of some other economic activities, the relaxing of some restrictions on personal movements, but the continuation of the blocking of bar, restaurants, social, sport and cultural public events, and of the closure of school and universities, with the exception of on-line activities.

In conclusion, the government reacted with some vigor to the pandemics too late, only about five crucial weeks after the discovery of the contagion in the group of Chinese tourists visiting Italy. Most likely, in January and the first half of February the pandemics had been already expanding in an undetected, creeping and insidious way in Northern Italy through a number of direct and indirect commercial, touristic and human relations between China and Italy, flourishing in particular in the richest and most industrialized part of the country.

Moreover, five fatal mistakes had been made, with the partial exception of Veneto, by our central and regional authorities a) a tardive, badly coordinated and poorly organized preparation of adequate personal protection devices, tests, ventilators, extra hospital beds and ICUs; b) a strategic approach mainly based on hospitals and families, with no adequate and well-organized filters to prevent the diffusion of the contagion within the overwhelmed hospitals and the families in the Covid-19 worst-hit zones; c) the neglect of the dramatic situation emerging in several old people’s homes, which had insufficient and inadequate staff and resources to contrast the internal diffusion of the pandemic; d) the initial lack of personal protections and tests even for doctors and nurses, which contributed to diffuse the contagion in hospitals, medical offices and old people’s homes and led to the death of 163 physicians and over 50 nurses and auxiliary personnel as of May 14; d) the great delay in preparing apps and qualified personnel able to trace the contacts of infected people in order to be able to contrast a rapid diffusion of the pandemic.

The situation had been greatly worsened by two structural factors. First of all, Italy, owing to a high public debt, aggravated by the severe 2008-9 financial crisis and the consequent “great recession”, and to the short- sighted policy of drastically cutting health costs, had progressively reduced the number of hospitals, limited the number of hospital beds and ICUs and reduced the quality of health services, especially for poor people. On the eve of the coronavirus crisis, Italy had less than one fourth of South Korean and Japanese hospital beds for 1,000 inhabitants and less than half the level of Germany. The lack of reserves in hospital beds, space and specialized personnel, had made very difficult to rapidly convert a part of beds to ICUs and to promptly acquire ventilators and the other necessary medical appliances to fight the pandemic. Secondly, in particular in Lombardy, for several years the regional authorities have progressively built a mixed public-private health system, which has in normal times a relative efficiency for well-off people and points of medical excellence, but also has progressively reduced the share of resources going to the public health sector, has fed several corruption cases, has too severely cut reserves in the public service, has increased waiting-time and the quality of services for most public health interventions and strongly weakened the territorial health system. Therefore, Lombardy had much poorer possibility of reacting to the pandemic than, for example, Veneto, which had maintained a larger presence of public health services and a stronger territorial health system.[13]

Conclusions

As a deadly game of skittles, Covid-19 moved from China, then went to East Asian countries, then to Europe and the Americas and to numerous other countries in the world, generating a great number of deaths and the partial disruption of social- economic systems. One problem is: why had not each skittle, when proudly erect, readily and fully profited from the experiences of the preceding skittles? China had been slow and reticent to inform the world, but from January 23, 2020 - the lockdown of Wuhan-,[14] everybody knew. In Europe and in the United States since the Northern Italian disaster, everybody knew. Why have so many countries and regions reacted so late and so poorly?

References

Alleva G., Arbia G., Falorsi P.D., Pellegrini G., Zuliani A., Proposta di una indagine a campione per una stima affidabile dei parametri fondamentali della epidemia da Sars-CoV-2, https://www.eticapa.it/eticapa/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Proposta-esperti-statistici.pdf

Cereda D., et al. (2020), The Early Phase of the Covid-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy, March 20. Preprint q-bio.PE , https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.09320v1

CREA Sanità, Osservatorio sui tempi di attesa e sui costi delle prestazioni sanitarie nei Sistemi sanitari regionali, I Report, Roma, https://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato2112108.pdf

Crisanti A, Cassone A. (2020), In one Italian town, we showed mass testing could eradicate the coronavirus, The Guardian, March 20, 2020.

Crisanti A., Dorigatti I. et al. (2020), Suppression of Covid-19 outbreak in the municipality of Vo’, Italy, preprint medRxiv, April 18. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.17.20053157v1

Fagiuoli S., Lorini F. , Remuzzi G. (2020), Adaptation and Lessons in the Province of Bergamo, The New England Journal of Medicine, Correspondence, May 5, 2020. Nejm.org.

Ferguson N., Bhatt S. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/mrc-gida/2020-03-30-COVID19-Report-13.pdf

Giles C., (2020), UK coronavirus deaths more than double official figure, according to FT study, Financial Times, April 22. https://www.ft.com/content/67e6a4ee-3d05-43bc-ba03-e239799fa6ab

Huang C. et al (2020), Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, Lancet, 395: 495 -506, published on-line January 24, 2020.

ISTAT-ISS (2020), https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/05/Rapporto_Istat_ISS.pdf

Kim Hyunjung (2020), https://globalbiodefense.com/2020/03/16/united-states-lessons-learned-covid-19-pandemic- response-south-korea-japan-observations-hyunjung-kim-gmu-biodefense/

Ministero della salute – CCM, (2020), Mortalità giornaliera (SiSMG) ed analisi della mortalità cumulativa nelle città italiane in relazione all’epidemia di Covid-19, Settimo Rapporto, Roma. http://www.deplazio.net/images/stories/SISMG/SISMG_COVID19.pdf

Normile D. (2020) https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/coronavirus-cases-have-dropped-sharply-south-korea-whats-secret-its-success

Our world in data (2020), https://covid.ourworldindata.org/data/owid-covid-data.csv.

Republic of Korea, Coronavirus disease-19 (2020), http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en

World Bank, 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO.ZS.

World Meters (2020), https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

Wu J. et al. 74,000 missing deaths: tracking the true toll of the coronavirus, New York Times, updated May 18, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/21/world/coronavirus-missing-deaths.html

[1]

[2] On the policies of South Korea, compared with those of Japan, see, for example, Kim Hyunjung (2020), https://globalbiodefense.com/2020/03/16/united-states-lessons-learned-covid-19-pandemic-response-south-korea-japan-observations-hyunjung-kim-gmu-biodefense/. See also, for South Korea, < http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en > and Normile D. (2020) https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/coronavirus-cases-have-dropped-sharply-south-korea-whats-secret-its-success

[3] See Ferguson N., Bhatt S. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/mrc-gida/2020-03-30-COVID19-Report-13.pdf

[4] The comparison between testing in Italy and South Korea is not easy, because the data are partially heterogenous. Anyhow, up to the last days of March, the tests of South Korea were higher than the Italian ones. In April and May, Italy had rapidly increased the number of tests, performing more tests than South Korea, but it did so mostly in a passive way, trying to keep up with the explosion of infected people and mainly testing symptomatic cases, with the partial exception of the Veneto region which tried to test also asymptomatic people. For the data, see: https://covid.ourworldindata.org/data/owid-covid-data.csv

[5] On April 1st 2020, two former presidents of ISTAT, the Italian Statistical Institute, Giorgio Alleva and Alberto Zuliani and other experts have advanced a detailed proposal for a national survey on coronavirus, which has not yet been carried on by the Italian authorities. See https://www.eticapa.it/eticapa/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Proposta-esperti-statistici.pdf

[6] On the case of Vo’, see Crisanti A., Dorigatti I. et al. (2020), See also Crisanti A, Cassone A. (March 20, 2020).

[7] As regards Italy for the period 20th February- 31 March 2020 we have almost complete data of the excess of the total observed deaths with respect to the deaths occurred in the same period in the preceding 5 years, (see par. 7, Table 3), and up to Mid-April 2020 we have partial data for 19 cities in Northern and Center-South Italy. (see http://www.deplazio.net/images/stories/SISMG/SISMG_COVID19.pdf). All these data confirm that the coronavirus pandemics had struck much more badly in Northern cities and provinces, such as Bergamo, Cremona, Lodi, Brescia, Milano, Alessandria, Turin, than in most cities and zones in the Center-South, with the partial exception of Urbino-Pesaro and Bari, and that the excess of deaths directly and indirectly due to coronavirus was consistently higher than the official estimates of coronavirus deaths.

For the United Kingdom a study of the Financial Times estimated that from March 16 up to April 21, 2020 coronavirus might have caused about 41,000 deaths, over the double of the hospital deaths of people positive to the tests (17,337). See https://www.ft.com/content/67e6a4ee-3d05-43bc-ba03-e239799fa6ab.

An analysis of the “New York Times” permits to estimate the percent differences between the excess deaths over the preceding 5 years and the official reported Covid-19 data. The differences are all positive and vary significantly among countries: 13% (Sweden), 20% (France), 25% (New York City and Spain), 32% (Germany), 46% (UK), 79% (Italy), 87% (Netherlands), but the data are calculated for different periods during the pandemic time. See Wu et al. (2020). https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/21/world/coronavirus-missing-deaths.html updated May 18,2020.

[8] In 2018 the share of people of 65 + years in the population was: China (10.9), South Korea (14.4), Italy (22.8) and Japan (27.6), Source World Bank, 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO.ZS

[9] Germany is a partial exception between the large European countries. It was able to react better than other great EU countries to the pandemic. Yet, as of May 22, it had a total number of deaths per million inhabitants 20 times higher than South Korea. Also, smaller European countries, such as Greece and some Central and Northern EU countries had a relatively low Covid-19 death toll, but they had much less Chinese immigrants and less important economic relations with China than the major EU countries. In any case, as of May 15th, even Greece had over 3 times the number of deaths per million inhabitants of South Korea.

[10] On the early phase of the Covid-19 outbreak in Lombardy, see Cereda et al. (2020).

[11] See https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/05/Rapporto_Istat_ISS.pdf

[12] An interesting analysis on the dramatic situation in the province of Bergamo in March-April 2020 is presented in Fagiuoli, Lorini, Remuzzi (2020).

[13] On some important differences between the health systems of Lombardy, Veneto and other regions see, for example, CREA Sanità https://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato2112108.pdf

[14] On the clinical features of the outbreak of the pandemic in Wuhan, see, for example, Huang C. et al. (2020, January 24). However, It must be noted that, according to a report by the “South China Morning Post”, the first case of Covid-19 in China had probably occurred much earlier, on November 17, 2019.